-

History of:

- Resources about:

- More:

- Baby walkers

- Bakehouses

- Bed warmers

- Beer, ale mullers

- Besoms, broom-making

- Box, cabinet, and press beds

- Butter crocks, coolers

- Candle snuffers, tallow

- Clothes horses, airers

- Cooking on a peat fire

- Drying grounds

- Enamel cookware

- Fireplaces

- Irons for frills & ruffles

- Knitting sheaths, belts

- Laundry starch

- Log cabin beds

- Lye and chamber-lye

- Mangles

- Marseilles quilts

- Medieval beds

- Rag rugs

- Rushlights, dips & nips

- Straw mattresses

- Sugar cutters - nips & tongs

- Tablecloths

- Tinderboxes

- Washing bats and beetles

- Washing dollies

- List of all articles

Subscribe to RSS feed or get email updates.

Poorer people used the combination of a chunk of flint, a piece of bent steel, and a tin cup of tinder. With pioneers the lock of the gun did duty instead. The unfortunates who had neither tinder box nor firearm tried to keep a constant supply of live coals, and, in the event of losing the fire, applied to a neighbor for a light.

Charles Winthrop Sawyer, Firearms in America, 1910

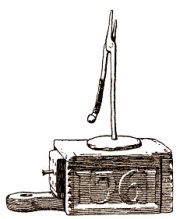

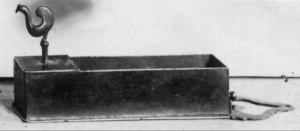

Unusual tinderbox with rushlight holder fixed on top. 1761 date carved on the side. Possibly English.

The Book of Non-Electric Lighting by Tim Matson

from Amazon.comor Amazon UK

The flint was a bit of stone...roughly shaped, oblong, square, or round, about two inches in diameter with a sharp edge, which was smartly struck against the steel. This latter object was hung over the the fingers of the left hand and the handle of it firmly grasped; the flint was held between the finger and thumb of the right hand, and the steel struck quickly with the flint from above downward. This caused the sparks to fall upon the tinder in the box...

N. Hudson Moore, The Collector's Manual, 1906

Among the colonists scorched linen was a favorite tinder to catch the spark of fire; and...all the old cambric handkerchiefs, linen underwear, and worn sheets of a household were carefully saved for this purpose.

Alice Morse Earle, Home Life in Colonial Days, 1898

From Fireplace to Cookstove by Priscilla Brewer

from Amazon.comor Amazon UK

Tinderboxes in the home

Flint, steel, and tinder for indoor lighting and heating: boxes, dampers, charred

linen

If you’ve ever got up on a cold,

dark morning and flipped a switch or struck a match, you’ll be glad you’re living

after the mid-19th century. Once upon a time, anyone in a northern winter who didn’t

keep a fire burning all night had to start the day by clashing flint on steel to

make a spark. Or at least one person in the household did.

If you’ve ever got up on a cold,

dark morning and flipped a switch or struck a match, you’ll be glad you’re living

after the mid-19th century. Once upon a time, anyone in a northern winter who didn’t

keep a fire burning all night had to start the day by clashing flint on steel to

make a spark. Or at least one person in the household did.

They needed to catch a spark on some flammable tinder and then somehow transfer this hint of fire to a thin splint of wood or a scrap of cord. Blowing carefully on the tinder helped the spark grow into something more like a flame. An easier solution was to touch smouldering tinder with a sulphur-tipped "match" to get enough flame to light a candle. And then they could go ahead with kindling a fire.... Even in warm countries the food wouldn’t get cooked without spark, tinder, and flame.

In the morning early, before dawn, the first sounds heard in a small house were the click, click, click of the kitchen-maid striking flint and steel over the tinder in the box. When the tinder was ignited, the maid blew upon it till it glowed sufficiently to enable her to kindle a match made of a bit of stick dipped in brimstone [sulphur]. The cover was then returned to the box, and the weight of the flint and steel pressing it down extinguished the sparks in the carbon. The operation was not, however, always successful; the tinder or the matches might be damp, the flint blunt, and the steel worn; or, on a cold, dark morning, the operator would not infrequently strike her knuckles instead of the steel; a match, too, might be often long in kindling, and it was not pleasant to keep blowing into the tinder-box, and on pausing a moment to take breath, to inhale sulphurous acid gas, and a peculiar odour which the tinder-box always exhaled.

Sabine Baring-Gould, Strange Survivals, 1892, Devon, England

Could you afford to keep a candle or lantern burning all night? How long would a

rushlight last? Would a draught blow the light out? If you woke in a dark room,

how long would it take you to catch a spark and coax it into something that would

light a candle? Practice would help, of course, but it seems to have been a hassle

for many people.

Could you afford to keep a candle or lantern burning all night? How long would a

rushlight last? Would a draught blow the light out? If you woke in a dark room,

how long would it take you to catch a spark and coax it into something that would

light a candle? Practice would help, of course, but it seems to have been a hassle

for many people.

The maid is stirring betimes, and slipping on her shoes and her petticoat, gropes for the tinder box, where after a conflict between the steel and the stone she begets a spark, at last the candle lights.... Matthew Stevenson, The Twelve Months, c1661

Could you cope without a tinderbox?

Some people kept a fire, or tiled stove, burning all winter or even all year. It wasn't just for the warmth in cold weather. It must have been so convenient to take a light from the hearth, and fan the embers back to life without having to start another day by knocking stone on metal.

"Banking up" the fire meant preserving a smouldering heat overnight. You could do this in different ways: for instance, covering the fire with a dense layer of fuel or, more economically, using a thick blanket of ashes. In the morning you blew the embers back to life, and fed the fire.

If by ill fortune the fire in the fireplace became wholly extinguished through carelessness at night, some one, usually a small boy, was sent to the house of the nearest neighbor, bearing a shovel or covered pan, or perhaps a broad strip of green bark, on which to bring back coals for relighting the fire.

Alice Morse Earle, Home Life in Colonial Days, 1898

Keeping a fire going round the clock was not unusual in colonial America, and it was common in cooler European countries, except in big cities with regulations about putting out fires at night. In Scotland and Ireland keeping peat fires alive overnight, all year, had symbolic as well as practical importance, and suggested good luck and a welcoming home. In the Western Isles of Scotland the flint and steel were not widely used, even in the 18th century.

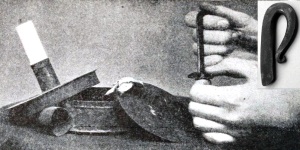

Steels aka firesteels

A piece of iron curved to fit over a hand and fingers could take various shapes.

Some were simple, others decorative. One classic shape (left) became a

heraldic symbol. Those used at home and kept in a box near the fireplace

or candle holder were usually quite plain. English and American tinderboxes often

held a simple hook-shaped firesteel that would hang over fingers. The human hand's

shape guaranteed similarities between steels in different cultures: look at this

fine Persian steel,

presumably not designed for the kitchen shelf.

A piece of iron curved to fit over a hand and fingers could take various shapes.

Some were simple, others decorative. One classic shape (left) became a

heraldic symbol. Those used at home and kept in a box near the fireplace

or candle holder were usually quite plain. English and American tinderboxes often

held a simple hook-shaped firesteel that would hang over fingers. The human hand's

shape guaranteed similarities between steels in different cultures: look at this

fine Persian steel,

presumably not designed for the kitchen shelf.

Flints

You needed a sharp-edged piece

of flint or other hard stone to strike a spark on the steel. Sometimes called a

strike-a-light (a name also used for the steel occasionally), it had to be kept sharp, or replaced. Writers often complained about

scraped knuckles and other wounds from flint hitting skin. Grumbling and cursing

came into the story too. While an experienced light-striker expected success within

3 minutes or so, the slightest dampness or other problem might extend that drastically.

You needed a sharp-edged piece

of flint or other hard stone to strike a spark on the steel. Sometimes called a

strike-a-light (a name also used for the steel occasionally), it had to be kept sharp, or replaced. Writers often complained about

scraped knuckles and other wounds from flint hitting skin. Grumbling and cursing

came into the story too. While an experienced light-striker expected success within

3 minutes or so, the slightest dampness or other problem might extend that drastically.

Tinder

Tinder could be anything dry and flammable. Charred rags were kept in many home tinderboxes. After cloth had been partly burnt the remnants were thin and relatively easy to light with a spark. Dried moss, leaves or fungus, and raw unspun flax were alternatives.

The domestic manufacture of the tinder was a serious affair. At due seasons, and very often if the premises were damp, a stifling smell rose from the kitchen, which, to those who were not intimate with the process, suggested doubts whether the house were not on fire. The best linen rag was periodically burnt, and its ashes deposited in the tinman's box, pressed down with a close fitting lid upon which the flint and steel reposed.

Household Words, c1850

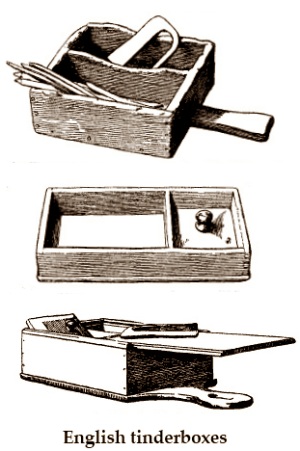

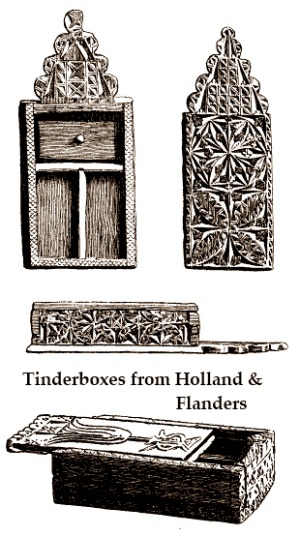

Boxes: wood, tin, brass

Tinderboxes for a man's pocket came in many different designs: some simple and

some for show, like today's lighters. But this article is about domestic tinderboxes

for people needing candlelight or fire at home. The most ornamental wooden ones

were found in Northern European countries with a tradition of folk art carving,

and were often hung on the wall. On Long Island, New York, Dutch-Americans had elaborately

carved tinderboxes in their homes, according to one memoir of the 1820s which also

describes tinder being kept in horns plugged with cloth.

Tinderboxes for a man's pocket came in many different designs: some simple and

some for show, like today's lighters. But this article is about domestic tinderboxes

for people needing candlelight or fire at home. The most ornamental wooden ones

were found in Northern European countries with a tradition of folk art carving,

and were often hung on the wall. On Long Island, New York, Dutch-Americans had elaborately

carved tinderboxes in their homes, according to one memoir of the 1820s which also

describes tinder being kept in horns plugged with cloth.

British tinderboxes for ordinary

homes and kitchens were

mostly plain. The round tin ones were as undecorated as the wooden boxes.

In Scotland and some regions of England the name was "tunder box" or "fire box".

British tinderboxes for ordinary

homes and kitchens were

mostly plain. The round tin ones were as undecorated as the wooden boxes.

In Scotland and some regions of England the name was "tunder box" or "fire box".

In late 18th century London you could buy a tin tinderbox with a steel and snuffers for eighteenpence, as advertised in The Times. These tin boxes were very common and have survived better than charred old wooden ones. In wealthier households there were brass, or even silver, tinderboxes in bedrooms and drawing rooms.

The old-fashioned cottage tinder-box was generally made of wood, about eight inches long, four inches wide, and two inches deep; divided in the middle; one compartment containing the steel, the flint, and matches; the other the tinder, and damper. Such, at least, was the form with which housekeepers were familiar eighty years ago; but as the box was often home-made, there were, of course, varieties; but I never saw a handsome one. Those sold at the shops were round, made of tin, and, besides the damper, had a lid, with a socket to hold a candle...I never saw either a costly or ornamental box of this class.

John Holland, On Tinder Boxes, 1866, England

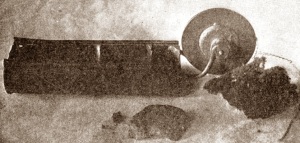

Goodbye to tinderboxes

Matches you could strike on sandpaper were invented in 1826, after various less

successful inventions for striking a light, including the tinder pistol and tinder

wheel (right), also called a mill in some US southern states. Friction matches took a few years

to catch on but then spread rapidly. A generation later, by 1850 or so, tinderboxes

were vanishing. The new matches, tipped with chemicals, were liberating.

Blackened old wood tinderboxes were broken up for firewood; tin boxes went to the

attic. Today, tinderboxes are irrelevant to normal domestic life, but people interested

in bushcraft, survival skills, and historical re-enactment still practise the art

of making fire with flint and steel.

Matches you could strike on sandpaper were invented in 1826, after various less

successful inventions for striking a light, including the tinder pistol and tinder

wheel (right), also called a mill in some US southern states. Friction matches took a few years

to catch on but then spread rapidly. A generation later, by 1850 or so, tinderboxes

were vanishing. The new matches, tipped with chemicals, were liberating.

Blackened old wood tinderboxes were broken up for firewood; tin boxes went to the

attic. Today, tinderboxes are irrelevant to normal domestic life, but people interested

in bushcraft, survival skills, and historical re-enactment still practise the art

of making fire with flint and steel.

>>>> Sulphur matches - a page about the sulphur-tipped sticks kept in tinderboxes

- Other pages on fire or light:

- Tallow candles and snuffers

- Rushlights

- Peat and turf fires

- Fireplaces

- Cooking outdoors with lime and no fire

5 April 2012

5 April 2012

You may like our new sister site Home Things Past where you'll find articles about antiques, vintage kitchen stuff, crafts, and other things to do with home life in the past. There's space for comments and discussion too. Please do take a look and add your thoughts. (Comments don't appear instantly.)

For sources please refer to the books page, and/or the excerpts quoted on the pages of this website, and note that many links lead to museum sites. Feel free to ask if you're looking for a specific reference - feedback is always welcome anyway. Unfortunately, it's not possible to help you with queries about prices or valuation.