-

History of:

- Resources about:

- More:

- Baby walkers

- Bakehouses

- Bed warmers

- Beer, ale mullers

- Besoms, broom-making

- Box, cabinet, and press beds

- Butter crocks, coolers

- Candle snuffers, tallow

- Clothes horses, airers

- Cooking on a peat fire

- Drying grounds

- Enamel cookware

- Fireplaces

- Irons for frills & ruffles

- Knitting sheaths, belts

- Laundry starch

- Log cabin beds

- Lye and chamber-lye

- Mangles

- Marseilles quilts

- Medieval beds

- Rag rugs

- Rushlights, dips & nips

- Straw mattresses

- Sugar cutters - nips & tongs

- Tablecloths

- Tinderboxes

- Washing bats and beetles

- Washing dollies

- List of all articles

Subscribe to RSS feed or get email updates.

Maggie told us how very important [threshing day] was in her childhood, for that was the day when all the old caff (chaff) beds were renewed. Early in the morning all the old chaff was emptied into the pig-sty; the bed-ticks were washed and dried in the sun...... even the bolster-shaped mattress from the cradle was emptied and washed. That night, after a long day in the sun, the ticks were filled by hand with clean chaff left by the thrashin' mill, and every member of the family who could ply a needle and thread sat down and worked till all were sewn up. Not until this was done could anybody go to bed!

(Describing the mid-19th century in Scotland) Amy Stewart Fraser, In Memory Long, 1977

Warm and Snug: The History of the Bed

From Amazon.com

Or from Amazon UK

The leaves of the chestnut tree make very wholesome mattresses to lie on... [Beech leaves]... being gathered about their fall, and somewhat before they are much frost-bitten, afford the best and easiest mattresses in the world to lay under our quilts instead of straw; because, besides their tenderness and loose lying together, they continue sweet for seven or eight years long; before which time straw becomes musty and hard; they are thus used by divers persons of quality in Dauphine; and in Switzerland I have sometimes lain on them to my great refreshment...

John Evelyn, Sylva: A discourse of forest-trees, 1670

Sleeping on straw

...or chaff, leaves, husks, rushes, palliasses...

Straw doesn't have to be stuffed into a mattress cover before you can sleep on it.

A loose heap seems very comfortable compared with sleeping on a hard floor - or

you can put the straw into a wooden bed with sides like the Danish one illustrated

below left, or

this Polish bed. You can also tie it into a mattress shape and cover it

with cloth.

Straw doesn't have to be stuffed into a mattress cover before you can sleep on it.

A loose heap seems very comfortable compared with sleeping on a hard floor - or

you can put the straw into a wooden bed with sides like the Danish one illustrated

below left, or

this Polish bed. You can also tie it into a mattress shape and cover it

with cloth.

There's often plenty of straw available after cereal crops have been harvested, and so it's been used for mattresses in many times and places: a kind of mattress just as familiar to ancient Romans as it was to British soldiers in World War Two. Chaff (husks separated from edible grains, and sometimes mixed with chopped straw since the invention of mechanical "chaff-cutters") is softer but not available in such quantities. Rice chaff has filled mattresses in Asia; oat chaff was traditional for Scottish caff-beds or cauf-secks (sacks).

Leaves were considered a good mattress-filler (see left-hand column), while reeds, bracken or seaweed were suitable choices in some regions. The Roman writer Pliny reported that spartum or esparto grass was used in Spain 2000 years ago, and this continued into the 19th century.

A simple sack, called a tick, is

all that most mattress covers have ever been. Canvas woven from hemp, also called

hurden or tow, was a likely choice for the tick before machine-woven cottons took

over. Ticking, the cloth for the tick, evolved into strong, closely-woven cotton,

often striped in English-speaking countries. The mattress might be called a palliasse,

or sometimes pallet, based on the French word for straw: paille. The name

palliasse applies particularly to a mattress used on its own, without a featherbed,

or solid bedstead.

A simple sack, called a tick, is

all that most mattress covers have ever been. Canvas woven from hemp, also called

hurden or tow, was a likely choice for the tick before machine-woven cottons took

over. Ticking, the cloth for the tick, evolved into strong, closely-woven cotton,

often striped in English-speaking countries. The mattress might be called a palliasse,

or sometimes pallet, based on the French word for straw: paille. The name

palliasse applies particularly to a mattress used on its own, without a featherbed,

or solid bedstead.

Using a straw mattress under a softer woollen or feather one was quite common by the 19th century, but it was a luxury in the 15th. Anne of Brittany had a fine bed herself, but her ladies-in-waiting slept on straw paillasses on the floor. Henry VII of England had a layer of straw under his featherbed, but his was not stuffed into a tick. His servants had to renew and check it daily:

The groom of the wardrobe brings in the loose straw and lays it reverently at the foot of the bed. The gentleman-usher draws back the curtains.Two squires stand by the bedhead and two yeomen of the guard at the foot. One of these, with the help of the yeomen of the chamber, carefully forms the truss, and rolls up and down on it to make it smooth and ensure that no dagger or such are hidden in it....A canvas is laid over the straw, then the feather-bed, which is smoothed with a bedstaff.

Lawrence Wright describing the household regulations of Henry VII in Warm & Snug:The History of the Bed, 1962

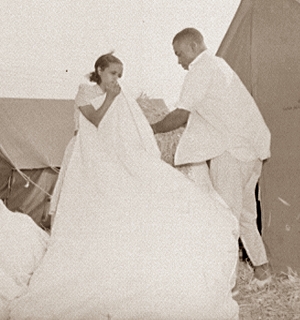

Refilling

a mattress with fresh straw, or other plant material, was a seasonal chore, undertaken

around harvest time. (See left-hand column) But some people were treated to more

frequent changes. Royal household account books from 16th century Scotland show

that fresh straw was issued to "the guard" surprisingly often: in some cases as

often as every fifteen days.

Refilling

a mattress with fresh straw, or other plant material, was a seasonal chore, undertaken

around harvest time. (See left-hand column) But some people were treated to more

frequent changes. Royal household account books from 16th century Scotland show

that fresh straw was issued to "the guard" surprisingly often: in some cases as

often as every fifteen days.

For travellers, carrying a tick with you and filling it with local stuffing may be a good plan. Many armies have operated like this, finding straw where they could. So too have some 19th century gentlemen explorers. In the 1880s Charles Wills advised travellers to Persia that, "No mattresses should ever be used, but as coarse chaff is procurable everywhere, large bags should be taken, the size of a mattress ...", and in the 1820s a navy captain from Philadelphia travelling across Russia was offered "a clean bed, made on the spot for my accommodation, by filling a tick with hay, and sewing it up again".

We used always to think that the most luxurious and refreshing bed is that which prevails universally in Italy, which consists of an absolute pile of mattresses, filled with the elastic spathe of Indian corn; we mean that delicate blade from which the large head of the plant bursts forth. These beds have the advantage of being soft as well as elastic, and we have always found the sleep enjoyed on them to be peculiarly sound and restorative; but the beds made of beech leaves are really no whit behind them in these qualities, while the fragrant smell of green tea, which the leaves retain, is most gratifying. The only objection to them is, the slight crackling noise which they occasion when a person turns in bed...

Sir Thomas Lauder, quoted in Webster's Encyclopædia of Domestic Economy, c1844

9 January 2008

9 January 2008

You may like our new sister site Home Things Past where you'll find articles about antiques, vintage kitchen stuff, crafts, and other things to do with home life in the past. There's space for comments and discussion too. Please do take a look and add your thoughts. (Comments don't appear instantly.)

For sources please refer to the books page, and/or the excerpts quoted on the pages of this website, and note that many links lead to museum sites. Feel free to ask if you're looking for a specific reference - feedback is always welcome anyway. Unfortunately, it's not possible to help you with queries about prices or valuation.