-

History of:

- Resources about:

- More:

- Baby walkers

- Bakehouses

- Bed warmers

- Beer, ale mullers

- Besoms, broom-making

- Box, cabinet, and press beds

- Butter crocks, coolers

- Candle snuffers, tallow

- Clothes horses, airers

- Cooking on a peat fire

- Drying grounds

- Enamel cookware

- Fireplaces

- Irons for frills & ruffles

- Knitting sheaths, belts

- Laundry starch

- Log cabin beds

- Lye and chamber-lye

- Mangles

- Marseilles quilts

- Medieval beds

- Rag rugs

- Rushlights, dips & nips

- Straw mattresses

- Sugar cutters - nips & tongs

- Tablecloths

- Tinderboxes

- Washing bats and beetles

- Washing dollies

- List of all articles

Subscribe to RSS feed or get email updates.

. . . shee that wanteth a sleeke-stone to smooth hir linnen, wil take a pebble . . . (a woman with no sleekstone to smooth her linen will use a pebble)

John Lyly, Euphues and his England, 1580

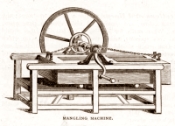

It consisted of a large flat box fully three feet long and eight or ten inches high filled with heavy stones. Underneath were wooden rollers called “pins” three or four inches in diameter. The articles to be mangled were carefully wrapped round the pins and the box was, by a rope pulley, drawn back and forward over the pins which revolved under it. The charge for mangling was one half-penny per pinfull!

Robert S. Young, About Kinross-shire and its Folk, 1948

TUESDAY: IRONING

In most Iowa homes this third day of the week is reserved for ironing. The whole day should be reserved to complete this job.

The Iowa Housewife, 1880

...a large fire, of charcoal and hardwood, (unless furnaces or stoves are used;) a hearth, free from cinders and ashes, a piece of sheet-iron, in front of the fire, on which to set the irons, while heating; (this last saves many blackspots from careless ironers;) three or four holders, made of woollen and covered with old silk, as these do not easily take fire; two iron rings, or iron-stands, on which to set the irons, and small pieces of board to put under them, to prevent scorching the sheet; linen or cotton wipers; and a piece of beeswax, to rub on the irons when they are smoked. There should be, at least, three irons for each person ironing...

Catherine Beecher, A Treatise on Domestic Economy , 1842

Why should not the little lady have her little ironing-box, and undertake the ironing of the pocket-handkerchiefs?

Harriet Martineau, Household Education 1861

History of ironing

No-one can say exactly

when people started trying to press cloth smooth, but we know that the Chinese were

using hot metal for ironing before anyone else. Pans filled with hot coals were

pressed over stretched cloth as illustrated in the drawing to the right. A thousand

years ago this method was already well-established.

No-one can say exactly

when people started trying to press cloth smooth, but we know that the Chinese were

using hot metal for ironing before anyone else. Pans filled with hot coals were

pressed over stretched cloth as illustrated in the drawing to the right. A thousand

years ago this method was already well-established.

Meanwhile people in Northern Europe were using stones, glass and wood for smoothing. These continued in use for "ironing" in some places into the mid-19th century, long after Western blacksmiths started to forge smoothing irons in the late Middle Ages.

>>mangles >> flat-irons

& sad-irons >> box irons

>> ironing in Asia

>>>>irons for frills

>>>> ironing boards >>>>

early electric irons

Also: >>>> history of laundry and >>>> laundry from 1800

Linen smoothers: stones, glass, presses

Flattish hand-size stones could be rubbed over woven cloth to smooth it, polish it, or to press in pleated folds. Simple round linen smoothers made of dark glass have been found in many Viking women's graves, and are believed to have been used with smoothing boards. Archaeologists know there were plenty of these across medieval Europe, but they aren't completely sure how they were used. Water may have been used to dampen linen, but it is unlikely the smoothers were heated.

More recent

glass smoothers often had handles, like

these from Wales, or the English one in the picture (left).

They were also called slickers, slickstones, sleekstones, or slickenstones. Decorative

18th and 19th century glass smoothers in "inverted mushroom" shape may turn up at

antiques auctions. Occasionally they are made of marble or

hard wood.

More recent

glass smoothers often had handles, like

these from Wales, or the English one in the picture (left).

They were also called slickers, slickstones, sleekstones, or slickenstones. Decorative

18th and 19th century glass smoothers in "inverted mushroom" shape may turn up at

antiques auctions. Occasionally they are made of marble or

hard wood.

Slickstones

were standard pieces of laundering equipment in the late Middle Ages, in England

and elsewhere, and went on being used up to the 19th century, long after the introduction

of metal irons. They were convenient for small jobs when you didn't want to heat

up irons, lay out ironing blankets on boards, and so on.

Slickstones

were standard pieces of laundering equipment in the late Middle Ages, in England

and elsewhere, and went on being used up to the 19th century, long after the introduction

of metal irons. They were convenient for small jobs when you didn't want to heat

up irons, lay out ironing blankets on boards, and so on.

Other methods were available to the rich. Medieval launderers preparing big sheets, tablecloths etc. for a large household may have used frames to stretch damp cloth smooth, or passed it between "calenders" (rollers). They could also flatten and smooth linen in screw-presses of the kind known in Europe since the Romans had used them for smoothing cloth. Later presses (see right) sometimes doubled as storage furniture, with linen left folded flat under the board after pressing even when there were no drawers.

Mangle boards, box mangles

Even in modest homes with no presses, large items needed to be tackled with something

bigger than a slickstone. They could be smoothed with a

mangle board and rolling pin combination; many wonderfully carved antique

Scandinavian or Dutch mangle boards have been preserved by collectors. The board,

often carved by a young man for his bride-to-be, was pressed back and forth across

cloth wound on the roller.

Even in modest homes with no presses, large items needed to be tackled with something

bigger than a slickstone. They could be smoothed with a

mangle board and rolling pin combination; many wonderfully carved antique

Scandinavian or Dutch mangle boards have been preserved by collectors. The board,

often carved by a young man for his bride-to-be, was pressed back and forth across

cloth wound on the roller.

In England boards, paddles or bats like these were called battledores, battels, beatels, beetles, or other "beating" names. In Yorkshire a bittle and pin was used in the same way as the Scandinavian mangle board and roller. The earlier mechanical mangles copied this method of pressing a flat surface across rollers. The box mangle was a heavy box weighted with stones functioning as the "mangle board", with linen wound on cylinders underneath, or spread under the rollers. The boards/bats used for smoothing were similar to wooden implements used in washing: washing beetles used to beat clothes clean, perhaps in a stream. Sometimes they were cylindrical like the mangle rollers, sometimes flat. Instead of pressing you could simply whack your household linen with a bat/paddle against a flat surface, as witnessed in the Scottish Borders in 1803 by Dorothy Wordsworth.

Early box mangles (see left-hand column), like Baker's Patent

Mangle, were devised for pressing and smoothing. Mangles with two rollers

(above left) could also be used for wringing water out of fabric. Many Victorian

households would complete the "ironing" of sheets and table-linen with a mangle,

using hot irons just for clothing. In the UK laundry could be sent for smoothing

to a mangle-woman, working at home, often a widow earning pennies with a mangle

bought by well-wishers after her husband's death. In the late 19th/early 20th century

US commercial laundries described the mangling or pressing of large items as "flatwork"

to distinguish it from the detailed ironing given to shaped clothing.

>>>> more on mangles and

mangle boards

Flat irons, sad irons

Blacksmiths started forging

simple flat irons in the late Middle Ages. Plain metal irons were heated by a fire

or on a stove. Some were made of stone, like these

soapstone irons from Italy. Earthenware and terracotta were also used, from

the Middle East to France

and the Netherlands.

Blacksmiths started forging

simple flat irons in the late Middle Ages. Plain metal irons were heated by a fire

or on a stove. Some were made of stone, like these

soapstone irons from Italy. Earthenware and terracotta were also used, from

the Middle East to France

and the Netherlands.

Flat irons were also called sad irons or smoothing irons. Metal handles had to be gripped in a pad or thick rag. Some irons had cool wooden handles and in 1870 a detachable handle was patented in the US. This stayed cool while the metal bases were heated and the idea was widely imitated. (See these irons from Central Europe.) Cool handles stayed even cooler in "asbestos sad irons". The sad in sad iron (or sadiron) is an old word for solid, and in some contexts this name suggests something bigger and heavier than a flat iron. Goose or tailor's goose was another iron name, and this came from the goose-neck curve in some handles. In Scotland people spoke of gusing (goosing) irons.

You'd need at least two irons on the go together for an effective system: one in use, and one re-heating. Large households with servants had a special ironing-stove for this purpose. Some were fitted with slots for several irons, and a water-jug on top.

At home, ironing traditional fabrics without the benefit of electricity was a hot, arduous job. Irons had to be kept immaculately clean, sand-papered and polished. They must be kept away from burning fuel, and be regularly but lightly greased to avoid rusting. Beeswax prevented irons sticking to starched cloth. Constant care was needed over temperature. Experience would help decide when the iron was hot enough, but not so hot that it would scorch the cloth. A well-known test was spitting on the hot metal, but Charles Dickens describes someone with a more genteel technique in The Old Curiosity Shop. She held "the iron at an alarmingly short distance from her cheek, to test its temperature..."

The same straightforward

"press with hot metal" technique can be

seen in Egypt where a few traditional "ironing men" (makwagi) still

use long, heavy pieces of iron, pressed across the cloth with their feet. Berber

people in Algeria traditionally use heated

metal ovals on long handles, called fers kabyles (Kabyle irons) in

France, where they were adopted for intricate ironing tasks.

The same straightforward

"press with hot metal" technique can be

seen in Egypt where a few traditional "ironing men" (makwagi) still

use long, heavy pieces of iron, pressed across the cloth with their feet. Berber

people in Algeria traditionally use heated

metal ovals on long handles, called fers kabyles (Kabyle irons) in

France, where they were adopted for intricate ironing tasks.

Box irons, charcoal irons

If you make the base of your iron into a container you can put glowing coals inside it and keep it hot a bit longer. This is a charcoal iron, and the photograph (right) shows one being used in India, where it's not unusual to have your ironing done by a "press wallah" at a stall with a brazier nearby. Notice the hinged lid and the air holes to allow the charcoal to keep smouldering. These are sometimes called ironing boxes, or charcoal box irons, and may come with their own stand.

For centuries charcoal irons have been

used in many different countries. When they have a funnel to keep smokey smells

away from the cloth, they may be called chimney irons. Antique charcoal irons are

attractive to many collectors, while modern charcoal irons are manufactured in Asia

and also used in much of Africa. Some of these are sold to Westerners as reproductions

or replica "antiques".

For centuries charcoal irons have been

used in many different countries. When they have a funnel to keep smokey smells

away from the cloth, they may be called chimney irons. Antique charcoal irons are

attractive to many collectors, while modern charcoal irons are manufactured in Asia

and also used in much of Africa. Some of these are sold to Westerners as reproductions

or replica "antiques".

Some irons were shallower boxes and had fitted "slugs" or "heaters" - slabs of metal - which were heated in the fire and inserted into the base instead of charcoal. It was easier to keep the ironing surface spotlessly clean, away from the fuel, than with flatirons or charcoal irons. Brick inserts could be used for a longer-lasting, less intense heat. These are box or slug irons, once known as ironing boxes too. In some countries they are called ox-tongue irons after a particular shape of insert.

Late 19th century iron designs experimented with heat-retaining fillings. Designs of this period became more and more ingenious and complicated, with reversible bases, gas jets and other innovations. See some inventive US models here. By 1900 there were electric irons in use on both sides of the Atlantic.

>>>> more on early electric irons

>>>> more on charcoal iron design

Ironing in Asia

Ironing continued to be done with hot coals in open metal pans in China, the basic

principles no different from an enclosed charcoal iron.

Pan irons could be simple or highly decorative. Further west, clay smoothers

were sometimes used. Solid ones could be heated for pressing. Others were designed

to hold hot embers like the North African terracotta iron on

this page. The ladies preparing newly-woven silk in a

12th century Chinese painting are using a pan iron, in the same way

as the ironers in the 19th century drawing at the top of this page. Although that

drawing comes from Korea, Koreans were traditionally known for smoothing their clothes

with pairs of

ironing sticks, beating cloth rhythmically on a stone support. A single

club for beating clothes smooth was used in Japan, on a stand called a

kinuta. In many parts of the world similar techniques were used in

both cloth manufacturing and laundering: in

Senegal, for example.

>>>> more on ironing in Korea and Japan

>>>> irons for frills

>>>> ironing boards

>>>> history of starch

>>>> 19th century mangles

Also: >>>> history of laundry and >>>> laundry from 1800

You may like our new sister site Home Things Past where you'll find articles about antiques, vintage kitchen stuff, crafts, and other things to do with home life in the past. There's space for comments and discussion too. Please do take a look and add your thoughts. (Comments don't appear instantly.)

For sources please refer to the books page, and/or the excerpts quoted on the pages of this website, and note that many links lead to museum sites. Feel free to ask if you're looking for a specific reference - feedback is always welcome anyway. Unfortunately, it's not possible to help you with queries about prices or valuation.