-

History of:

- Resources about:

- More:

- Baby walkers

- Bakehouses

- Bed warmers

- Beer, ale mullers

- Besoms, broom-making

- Box, cabinet, and press beds

- Butter crocks, coolers

- Candle snuffers, tallow

- Clothes horses, airers

- Cooking on a peat fire

- Drying grounds

- Enamel cookware

- Fireplaces

- Irons for frills & ruffles

- Knitting sheaths, belts

- Laundry starch

- Log cabin beds

- Lye and chamber-lye

- Mangles

- Marseilles quilts

- Medieval beds

- Rag rugs

- Rushlights, dips & nips

- Straw mattresses

- Sugar cutters - nips & tongs

- Tablecloths

- Tinderboxes

- Washing bats and beetles

- Washing dollies

- List of all articles

Subscribe to RSS feed or get email updates.

Wood's patent on which Beetham's washing mill was based:

The machine consists generally of a tub or vessel with a curved bottom, which contains the soap suds and the cloth to be cleansed. A frame is suspended, the lower part of which having pressers attached is caused to move backwards and forwards in the tub by means of a wheel and crank, and thereby to agitate and compress the cloth against the sides of the tub, and work it backwards and forwards till cleansed.

1790 patent, summarised in 1859

Lee M Maxwell, Save Women's Lives: History of Washing Machines, from Amazon.comor Amazon UK

The Governors of St James Workhouse, Clerkenwell

... Between the hours of nine in the morning and nine at night, in a common Mill of six guineas value [Beetham's], ...consuming only nine and a half pounds of soap and a pound of pearl ashes...wrung in a common wringer, value 1 guinea...

350 shirts and shifts, each worn a week

64 aprons, ditto

36 handkerchiefs

10 gowns

10 frocks

2 long table cloths

48 sheets, worn a month

caps and other small things...

The same quantity by hand always took seven women two days...[but no mention of how many people worked with the machine]

Diary or Woodfall's Register, 1792

Patricia E. Malcolmson, English Laundresses: A Social History, 1850-1930 from Amazon.com

or Amazon UK

Arwen Mohun, Steam Laundries: Gender, Technology, and Work in the United States and Great Britain, 1880-1940, from Amazon.comor Amazon UK

History of washing machines up to 1800

Early washing machines, inventors, advertising, washerwomen

This is not just a story of inventions, inventors and their patents. Patents don't

tell us enough about the earliest washing machines. We want to know what machines

were actually manufactured. Who sold them? Who bought them? Did people like them?

This is not just a story of inventions, inventors and their patents. Patents don't

tell us enough about the earliest washing machines. We want to know what machines

were actually manufactured. Who sold them? Who bought them? Did people like them?

Before 1800 not many people had seen a washing machine, let alone used one. For another century after that they were not found in many homes, even in developed countries where the industrial revolution was well under way. Some of the earliest went to institutions as well as private houses. A 1790s British washing machine ad targeted "the guardians of all charitable foundations, the governors of all public hospitals, and the commanders of ships and vessels appointed to long voyages".

Mechanising laundry work raised social questions. How would this affect the poorest women of all, who depended on employment as laundresses? Two of the earliest washing machine promoters, Schäffer and Beetham (see below), felt they should discuss this when they were writing about the advantages of their machines. A satirical writer also commented:

Improvements were always received by the wisest in the world, whilst the prejudiced part...would for ever be inimical to reformation. ...The marvellous washing mill of Beetham's...has met the curses, execrations, and anathema of all the old laundresses, and young linen drapers in London: what then? Is not its utility apparent to every apprentice in the laundry? Are the caps and aprons of your ladies...to be cruelly tortured and torn by the hands of a drunken washerwoman?

Thomas Hastings, The Regal Rambler, 1793

The idea of washing by machine goes back a long way, but nothing practical happened

until the mid-1700s. Before that, three early designs take turns being put forward as "first

washing machine ever". An early 17th century book by

Jacopo Strada's grandson Ottavio showed his 15th century idea for a washing

machine, probably intended for use in textile manufacturing. Then in the 1670s John Hoskins

experimented with putting fine laundry into a thick bag that could be soaked

before squeezing with a "wheel and cylinder" mechanism. A 1691 English patent referred

to an "engine" with a long list of possible uses, including clothes washing. But

patents were different then. No drawings were submitted, it is unlikely any washing

machine was made, and patents were more a nod of royal approval for someone's business

plans, than serious support for inventors. *

The idea of washing by machine goes back a long way, but nothing practical happened

until the mid-1700s. Before that, three early designs take turns being put forward as "first

washing machine ever". An early 17th century book by

Jacopo Strada's grandson Ottavio showed his 15th century idea for a washing

machine, probably intended for use in textile manufacturing. Then in the 1670s John Hoskins

experimented with putting fine laundry into a thick bag that could be soaked

before squeezing with a "wheel and cylinder" mechanism. A 1691 English patent referred

to an "engine" with a long list of possible uses, including clothes washing. But

patents were different then. No drawings were submitted, it is unlikely any washing

machine was made, and patents were more a nod of royal approval for someone's business

plans, than serious support for inventors. *

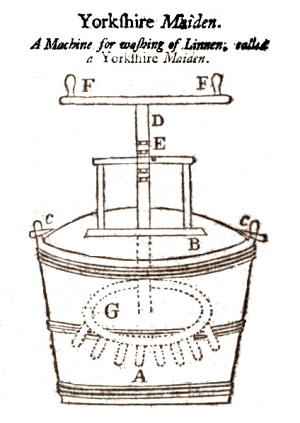

So, no relevance there to anyone tackling a heap of dirty laundry, as far as we can tell. It's not until the mid-1700s that we see signs of progress with labour-saving washing machines. Versions of the tub in the first picture were on sale in London by 1752, when it was said to have been "long in use" in the North of England.* It is clearly related to the washing dollies that were common home laundry tools in the 19th century.

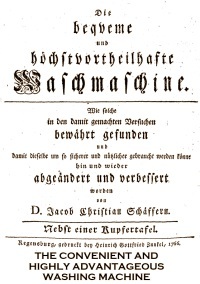

In Germany Jacob

Schäffer was inspired by a magazine article about a Danish version of an

English washing machine like the "Yorkshire Maiden" above. In 1766 he announced

his improved version (pictured left) in a book explaining its advantages, and describing

his experiments with washing different kinds of clothing. He was a little concerned

about the effect on washerwomen, but concluded they need not fear much loss of income.

They would still be needed to fill the tub, work the machine, hang laundry out to

dry, starch, iron and more, and their

health would benefit if they could stay dry while working in cold weather. His machine

would save on lye, fuel for heating water, soap

etc. Schäffer also wrote a book of letters, supposedly from one woman to her friend

about her wonderful new washing machine. He oversaw the manufacture of sixty machines

of this kind, and the design was successful enough to be manufactured in Germany

for another century, with slight adaptations. *

In Germany Jacob

Schäffer was inspired by a magazine article about a Danish version of an

English washing machine like the "Yorkshire Maiden" above. In 1766 he announced

his improved version (pictured left) in a book explaining its advantages, and describing

his experiments with washing different kinds of clothing. He was a little concerned

about the effect on washerwomen, but concluded they need not fear much loss of income.

They would still be needed to fill the tub, work the machine, hang laundry out to

dry, starch, iron and more, and their

health would benefit if they could stay dry while working in cold weather. His machine

would save on lye, fuel for heating water, soap

etc. Schäffer also wrote a book of letters, supposedly from one woman to her friend

about her wonderful new washing machine. He oversaw the manufacture of sixty machines

of this kind, and the design was successful enough to be manufactured in Germany

for another century, with slight adaptations. *

There were several English designs patented before 1800. Rogerson's (1780) and Sidgier's (1782) machines are two of the earliest. It is unclear whether Sidgier got any benefit from his innovative rotating drum design, though it was probably quite influential over the following decades. A turning cylinder with water passing through it, like Sidgier's, was the basic idea used for machines in many of the earliest hospital and commercial laundries.

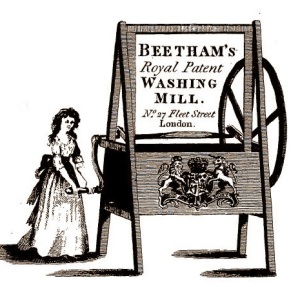

In 1787 an energetic washing machine publicist came on the scene.

Edward Beetham, ex-actor, writer, bookseller etc., hooked up with Thomas

Todd, who had just been granted a patent for a "machine for the washing and ironing

of linen, woollen and cotton stuffs, silks, carpets, and every other woven or knit

fabric". Beetham's PR campaign for machines sold by "Messrs. Todd, Beetham and Co.",

and later for his own, outdid Schäffer's promotional efforts in Germany and got

his products more attention than any other existing English washing machines. Beetham

advertised in The Times for October 10th that they had "brought to perfection":

In 1787 an energetic washing machine publicist came on the scene.

Edward Beetham, ex-actor, writer, bookseller etc., hooked up with Thomas

Todd, who had just been granted a patent for a "machine for the washing and ironing

of linen, woollen and cotton stuffs, silks, carpets, and every other woven or knit

fabric". Beetham's PR campaign for machines sold by "Messrs. Todd, Beetham and Co.",

and later for his own, outdid Schäffer's promotional efforts in Germany and got

his products more attention than any other existing English washing machines. Beetham

advertised in The Times for October 10th that they had "brought to perfection":

A machine for washing linen which will, in an equal space of time, wash as much linen as six or eight of the ablest washerwomen, without the use of lees [lye], and with only one third of the fire and soap.

...the common objection to machines, that they destroy the linen is, in the present invention, totally removed... entirely free from friction....works by pressure only...

Before long Beetham announced he was sole partner. In autumn 1790 he started advertising a "new patent portable washing mill". He had bought the rights to a patent granted to James Wood. (See LH column) Once a week he demonstrated this mill working "safely", sometimes with a bank bill in amongst the linen. He offered a variety of sizes and prices and a special "navy" version for shipboard use, and assured people they would save "15 shillings in every guinea" on laundry costs. "Patent chain net, for wringing" was also available. An anonymous book apparently written by Beetham quotes an acquaintance:

...the Washing Mill is not to be improved. The advantage of cleaning by pressure...your method...will not injure a cobweb...

...Before [my wife] had your mill, she employed three women full eighteen hours; by means of your mill the whole is performed much better in seven hours, by one servant, and a girl to turn the Mill, aged 11 years.

Observations on the utility of patents, and on the sentiments of Lord Kenyon respecting that subject. Including free remarks on Mr. Beetham's patent washing mills; and hints to those who solicit for patents. London, 1791

This washing machine certainly got attention, but it is hard to know how many homes

or institutions used one regularly. Beetham put a series of enthusiastic washing

machine ads in newspapers and on fliers. He said he had sold 1121 washing mills

in the year from May 1790 to 1791. Apparently 300 people liked them so much they

came back for another "in consequence of their entire approbration of the first,

and for their different houses". In 1792 he persuaded a

workhouse to publish a "satisfied customer" review. (See LH column)

A letter to an 1832 magazine said the writer still had one in "pretty good condition".

Did these machines all end up as firewood, or is there one around somewhere?

This washing machine certainly got attention, but it is hard to know how many homes

or institutions used one regularly. Beetham put a series of enthusiastic washing

machine ads in newspapers and on fliers. He said he had sold 1121 washing mills

in the year from May 1790 to 1791. Apparently 300 people liked them so much they

came back for another "in consequence of their entire approbration of the first,

and for their different houses". In 1792 he persuaded a

workhouse to publish a "satisfied customer" review. (See LH column)

A letter to an 1832 magazine said the writer still had one in "pretty good condition".

Did these machines all end up as firewood, or is there one around somewhere?

There was a bit of a washing machine trend in late 18th century London, though most people went on managing without. It wasn't just Beetham pressing the well-to-do public to buy. Rival ads appeared from Coates & Hancock. Each had independently patented different machines. Working together, they claimed their machines were so efficient there was no more need for hand-scrubbing cuffs and collars, and the gentle action meant the "finest muslins can be washed more safely than can possibly be done by hand". They offered a money-back guarantee for the first month after purchase.

Kendall also advertised his invention in 1791, calling it the Patent Laundress, and repeated the usual promises of safe methods and significant savings:

Patent Laundress, or Washing Machine

Is sold by Mr Kendall, the Inventor and Patentee

at No. 7, Charing-Cross, London

This ingenious Invention, made wholly of wood, is highly esteemed by men of science, and persons of every description; and without the parade of enumerating the saving qualities, it possesses them all, in the most eminent degree. The act of Wringing, so destructive to linen, is changed for Pressure, which cannot injure, and is made to fit the Machine or a Rincer, a most valuable appendage, which make it the completest Machine now known for the purpose of Washing.

Observer, 1791

Several more patents were granted in 1790s Britain, and there were other washing machines on sale too. Perhaps Beetham suffered from competition. By late 1791 his ads said that since people were imitating his idea, he would offer some lesser machines for half the price of the true patented originals. That would have brought the price of the smallest 8-shirt model down to 2 guineas: more than 6 weeks wages for a labourer, and about 2-3 weeks wages for a carpenter. (Several washing machine designers were carpenters or cabinet-makers.) The tide of advertising died down after 1793, though Beetham went on selling washing machines until at least 1808, alongside a patent mangle, churn, and "chiropedal car".

Cutting the costs of paid labour was a big selling point, and it was not only adult

washerwomen whose lives could be affected by this. The machines were considered

easy enough for a child to operate. Coates and Hancock said a girl of 12 could work

two of their machines more easily than a man could work one of any other sort. In

fact, a 7-year old could manage the job, they said. A girl would not have earned more

than a few pennies for a day's help.

Cutting the costs of paid labour was a big selling point, and it was not only adult

washerwomen whose lives could be affected by this. The machines were considered

easy enough for a child to operate. Coates and Hancock said a girl of 12 could work

two of their machines more easily than a man could work one of any other sort. In

fact, a 7-year old could manage the job, they said. A girl would not have earned more

than a few pennies for a day's help.

Coates and Hancock also patented their own wringing machines. Like Beetham's "chain net wringer", and rather like Hoskins' bag a century before, theirs were based on a netting or cloth wrapper for the laundry which was then twisted/turned/squeezed, more or less gently. Netting wringer designs continue into the 19th century, but the box mangle seems more like the forerunner of a classic wringer with rollers.

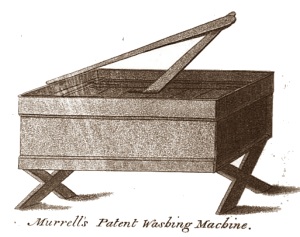

An 18th century enthusiasm for science and rational progress inspired some inventors. Murrell's machine (above left) was given a trial by, and described in the magazine of, a society for "the encouragement of agriculture, arts, manufactures and commerce" in the SW of England. The instructions for use are more objective than the newspaper ads. They admit some stains may need extra attention and end with "A stout lad or man may perform the more laborious part of the process". "Scientific" inventors were also developing washing mills for the textile industry.

Washing machines were not unheard of in late 18th century America, though the USA was yet to become a front-runner in laundry technology. Beetham's washing mill was advertised in ""Woods' Newark Gazette" (Newark, NJ's first newspaper) in 1791. A few years later came the first US patent related to washing clothes. This is the 1797 patent obtained by Nathaniel Briggs, mentioned on hundreds of websites. It's often said to be a washing machine, but we can't know for sure because a fire destroyed early US patent records.

Notes and sources - click here

Part 2 - from 1800 to the first electric machines - should be ready later in 2011.

You may also like:

History of Laundry up to 1800

History of Laundry in the 19th century

History of Ironing

Edward Beetham - a brief biography

14 April 2011

14 April 2011

You may like our new sister site Home Things Past where you'll find articles about antiques, vintage kitchen stuff, crafts, and other things to do with home life in the past. There's space for comments and discussion too. Please do take a look and add your thoughts. (Comments don't appear instantly.)

For sources please refer to the books page, and/or the excerpts quoted on the pages of this website, and note that many links lead to museum sites. Feel free to ask if you're looking for a specific reference - feedback is always welcome anyway. Unfortunately, it's not possible to help you with queries about prices or valuation.