-

History of:

- Resources about:

- More:

- Baby walkers

- Bakehouses

- Bed warmers

- Beer, ale mullers

- Besoms, broom-making

- Box, cabinet, and press beds

- Butter crocks, coolers

- Candle snuffers, tallow

- Clothes horses, airers

- Cooking on a peat fire

- Drying grounds

- Enamel cookware

- Fireplaces

- Irons for frills & ruffles

- Knitting sheaths, belts

- Laundry starch

- Log cabin beds

- Lye and chamber-lye

- Mangles

- Marseilles quilts

- Medieval beds

- Rag rugs

- Rushlights, dips & nips

- Straw mattresses

- Sugar cutters - nips & tongs

- Tablecloths

- Tinderboxes

- Washing bats and beetles

- Washing dollies

- List of all articles

Subscribe to RSS feed or get email updates.

One of the most really meritorious machines, was the Clothes Wringer, manufactured by the Metropolitan Washing Machine Co. It must save labouring women a great deal of severe labor. It is attached by screwing to the side of a wash-tub, and the clothes are passed by turning a handle, between two rollers covered with India rubber. The force required is slight, and by moderate motion a large sheet was passed through in five seconds. It was left slightly moist...

1861, Canadian Agriculturist

Messrs. Hotchkiss, Turner & Co., exhibited Spring-hinge Clothes-pins, a patent article, ingenious and well adapted to the object.

Connecticut State Agricultural Society, 1855

Lee M Maxwell, Save Women's Lives: History of Washing Machines, from Amazon.comor Amazon UK

... the clothes were brought forth to be washed, and for the first time I took my place at the washtub. It was not long before I rubbed the skin from my hands, and the pain and smart of the soap was intolerable; still I did not dare to complain. It was fortunate that I was called from the washtub frequently to do other work about the house, or I could not have gotten through the day.

Caroline Howard Gilman, Recollections of a Southern Matron, 1838

From Catharine Beecher to Martha Stewart: A Cultural History of Domestic Advice from Amazon.com

or Amazon UK

History of laundry - after 1800

Washing clothes and household linen: 19th century laundry methods and equipment

The information here follows on from

a page about the earlier history of laundry.

Both parts offer an overview of the way clothes and household linen were washed

in Europe, North America, and the English-speaking world, and are also a guide to

the other laundry history pages on this website. The links take you to more detailed

information and more pictures.

The information here follows on from

a page about the earlier history of laundry.

Both parts offer an overview of the way clothes and household linen were washed

in Europe, North America, and the English-speaking world, and are also a guide to

the other laundry history pages on this website. The links take you to more detailed

information and more pictures.

A tub of hot water, a washboard in a wooden frame with somewhere to rest the bar of laundry soap in pauses from scrubbing - this is a familiar image of how our great-grandmothers washed the laundry. It's not wrong, but it's only part of the picture. Factory-made washboards with metal or glass scrubbing surfaces certainly spread round the world in the 19th and early 20th centuries, and bars of soap were cheap and plentiful by the late 1800s, but there were other ways of tackling the laundry too.

In the idealised images of early advertising or today's nostalgia products, the

washtub is on a stand near a bright, breezy clothesline,

though in reality it may have been in a cramped kitchen or dark tenement courtyard,

or by a tumbledown shack. Alternatives to the classic washboard and tub included

dolly tubs (photo left) used with a dolly stick

(aka peggy or maiden) in the UK and parts of northern Europe. These were tall tubs,

also called possing- or maidening-tubs, in which large items were stirred and beaten with dollies or a plunger on a long handle.

In the idealised images of early advertising or today's nostalgia products, the

washtub is on a stand near a bright, breezy clothesline,

though in reality it may have been in a cramped kitchen or dark tenement courtyard,

or by a tumbledown shack. Alternatives to the classic washboard and tub included

dolly tubs (photo left) used with a dolly stick

(aka peggy or maiden) in the UK and parts of northern Europe. These were tall tubs,

also called possing- or maidening-tubs, in which large items were stirred and beaten with dollies or a plunger on a long handle.

Water could be heated in a large metal boiler or copper on a stove. A big pot boiling over an outdoor fire suited much of rural America. In urban areas there were public laundries: some with hot water and modern equipment, some much simpler and older, like the communal open-air sinks with a water supply in Italian cities. There were washing machines of a kind, but not many homes had them. Ideas from inventors working on washing machines helped improve the design of simple washboards and dollies. A plain wringer was the most common piece of home laundry machinery in 1900.

There were huge changes in domestic life between 1800 and 1900. Soap,

starch, and other aids to washing at home became more abundant and more

varied. Washing once a week on Monday or "washday"

became the established norm. As the Western world prospered, chemists, factory-owners

and advertisers invented and sold more laundry ingredients to more homes. English-speaking

countries saw riverside washing,

laundry bats, intermittent "great washes", and the use of

ashes and lye tail away. Later

Victorians thought these methods were old-fashioned or quaint. English travellers

sometimes described "foreign" laundry routines as very inferior to the "new" ones

they expected of their servants at home.

There were huge changes in domestic life between 1800 and 1900. Soap,

starch, and other aids to washing at home became more abundant and more

varied. Washing once a week on Monday or "washday"

became the established norm. As the Western world prospered, chemists, factory-owners

and advertisers invented and sold more laundry ingredients to more homes. English-speaking

countries saw riverside washing,

laundry bats, intermittent "great washes", and the use of

ashes and lye tail away. Later

Victorians thought these methods were old-fashioned or quaint. English travellers

sometimes described "foreign" laundry routines as very inferior to the "new" ones

they expected of their servants at home.

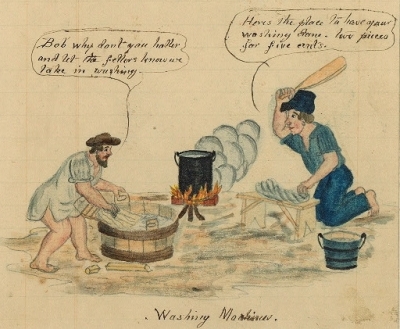

An 1864 sketch (right) from the American Civil War shows two soldiers hard at work, with equipment old and new. One is using a bat on a washing bench, an almost-forgotten method that was hardly used by the next generation in the USA and UK, though it survived longer in some parts of Europe, along with communal washing by rivers and in washhouses. The other soldier's tub and washboard, though, stayed popular for many years to come. Washboards were also used without a tub; they could be carried to the riverside.

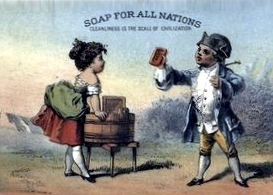

It may seem odd to say that

using soap generously was a modern, "advanced" way of tackling dirty laundry, but

in 1800 soap was used economically. It was mixed into hot water for the main wash,

and extra might be used for spot stain treatment, but everyday linen might still

be cleansed with ash lye. Some of the poorer people in Europe continued to wash

their "ordinary" things with no soap or minimal soap. Laundry soap was often the

cheap, soft, dark soap that was fairly easy to mix into hot water. Before the 19th

century hard soap could be made at home by people who had plenty of ashes and fat,

with warm, dry weather and salt to set the soap. If you bought it, you would buy

a piece cut from a large block.

It may seem odd to say that

using soap generously was a modern, "advanced" way of tackling dirty laundry, but

in 1800 soap was used economically. It was mixed into hot water for the main wash,

and extra might be used for spot stain treatment, but everyday linen might still

be cleansed with ash lye. Some of the poorer people in Europe continued to wash

their "ordinary" things with no soap or minimal soap. Laundry soap was often the

cheap, soft, dark soap that was fairly easy to mix into hot water. Before the 19th

century hard soap could be made at home by people who had plenty of ashes and fat,

with warm, dry weather and salt to set the soap. If you bought it, you would buy

a piece cut from a large block.

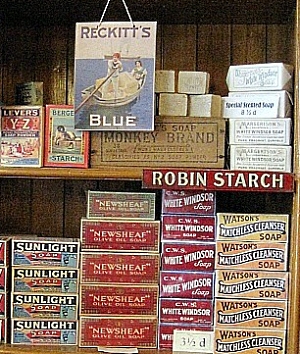

By the end of the century there were plenty of wrapped bars of commercial, branded laundry soap sold at moderate prices. To mix up a lather, you could grate flakes off the bar of soap, or even buy ready-made soap flakes in a box. Soap powder had been known for a few decades, and from about 1880 it was quite widely available. Developments in science, industry and commerce had a significant impact on household chores.

From the mid-nineteenth century, an overall increase in demand was one of the consequences of rising living standards. A growing concern for cleanliness, associated with health and with fashion in the form of whiteness for clothing items and linen, easily translated into widespread consumption, even as the low cost of soap, starch, and blue enabled their definition both as household necessities and as inputs to an expanding laundry industry.

Roy Church and Christine Clark, Product Development of Branded, Packaged Household Goods in Britain, 1870–1914, Enterprise & Society (Sep 2001)

Other changes in the course of the century included factory-made metal tubs starting

to replace wooden ones. Mass-produced tongs were more affordable and more likely to replace

sticks for lifting wet washing. Clotheslines, pegs, and pins became more widespread.

Home-made clothes pegs and indoor drying racks

were copied and/or improved by manufacturers supplying hardware stores. Improvements

in starch production led to a range of products with small differences, packaged

differently, and aimed at different users. Laundry blue

was no longer a mere ingredient in "blue starch". By the 1870s it was produced in

an array of different formats with different packaging gimmicks: wrapped squares,

balls, distinctive bags or bottles of liquid bluing. Tinted starches, dyes, and products

for restoring faded black clothes while you laundered them were on sale at prices

people with modest incomes could afford. Borax and washing soda were packaged under

various names. Borax was even used as a brand name for soaps and starches, and promoted

as a miracle all-purpose cleaning product.

Other changes in the course of the century included factory-made metal tubs starting

to replace wooden ones. Mass-produced tongs were more affordable and more likely to replace

sticks for lifting wet washing. Clotheslines, pegs, and pins became more widespread.

Home-made clothes pegs and indoor drying racks

were copied and/or improved by manufacturers supplying hardware stores. Improvements

in starch production led to a range of products with small differences, packaged

differently, and aimed at different users. Laundry blue

was no longer a mere ingredient in "blue starch". By the 1870s it was produced in

an array of different formats with different packaging gimmicks: wrapped squares,

balls, distinctive bags or bottles of liquid bluing. Tinted starches, dyes, and products

for restoring faded black clothes while you laundered them were on sale at prices

people with modest incomes could afford. Borax and washing soda were packaged under

various names. Borax was even used as a brand name for soaps and starches, and promoted

as a miracle all-purpose cleaning product.

There were laundry services aimed at the "middling" people too. While the upper

classes went on employing washerwomen and/or general

servants, there were various cheaper "send-out" laundry services in the

later 19th century and early 20th, including laundries that brought both domestic laundry and linen from hotels etc. to a "hand-finished" standard. The simplest were wet wash

(US) and bag wash (UK) arrangements where you sent off a bundle of dirty laundry

to be washed elsewhere. Ironing

was done at home at this bottom end of the market. In some places a

mangle woman with a box mangle would charge pennies for pressing household

linen and everyday clothing.

There were laundry services aimed at the "middling" people too. While the upper

classes went on employing washerwomen and/or general

servants, there were various cheaper "send-out" laundry services in the

later 19th century and early 20th, including laundries that brought both domestic laundry and linen from hotels etc. to a "hand-finished" standard. The simplest were wet wash

(US) and bag wash (UK) arrangements where you sent off a bundle of dirty laundry

to be washed elsewhere. Ironing

was done at home at this bottom end of the market. In some places a

mangle woman with a box mangle would charge pennies for pressing household

linen and everyday clothing.

See also:

Laundry history before 1800

History of Ironing

Site map with full list of laundry articles

If you want to know about one particular time and place, you may need to do more detailed research, but we hope you will find plenty of information on this site to get you started.

30 Sep 2010

30 Sep 2010

You may like our new sister site Home Things Past where you'll find articles about antiques, vintage kitchen stuff, crafts, and other things to do with home life in the past. There's space for comments and discussion too. Please do take a look and add your thoughts. (Comments don't appear instantly.)

For sources please refer to the books page, and/or the excerpts quoted on the pages of this website, and note that many links lead to museum sites. Feel free to ask if you're looking for a specific reference - feedback is always welcome anyway. Unfortunately, it's not possible to help you with queries about prices or valuation.