-

History of:

- Resources about:

- More:

- Baby walkers

- Bakehouses

- Bed warmers

- Beer, ale mullers

- Besoms, broom-making

- Box, cabinet, and press beds

- Butter crocks, coolers

- Candle snuffers, tallow

- Clothes horses, airers

- Cooking on a peat fire

- Drying grounds

- Enamel cookware

- Fireplaces

- Irons for frills & ruffles

- Knitting sheaths, belts

- Laundry starch

- Log cabin beds

- Lye and chamber-lye

- Mangles

- Marseilles quilts

- Medieval beds

- Rag rugs

- Rushlights, dips & nips

- Straw mattresses

- Sugar cutters - nips & tongs

- Tablecloths

- Tinderboxes

- Washing bats and beetles

- Washing dollies

- List of all articles

Subscribe to RSS feed or get email updates.

I won't have a hen's feather bed in the house . . . they're so soggy -like; it's 'nough to beat one all out to stir 'em up ev'ry day.

Anon, Rubina, 1864

...she had never learned the art of wrestling with a feather tick...

L.M.Montgomery, Anne of Green Gables, 1908

The use of this [eider] down is for making beds, but, particularly, for making what are called down quilts, a kind of covering, almost like a feather bed, which is used in the northern countries of Europe, as a protection against cold, instead of a common quilt or blanket.

William Bingley, Useful Knowledge: Or A Familiar Account of the Various Productions of Nature, Mineral, Vegetable, and Animal, which are chiefly employed for the use of Man, 1821

1395 - Lady Alice West of Hampshire leaves her daughter a bed with silk curtains and coverlet and her third best featherbed, with blankets, sheets and pillows

1448 - King Henry VI of England's usher of the chamber is granted ...a piece of black satin containing 15 yards, 2 chests with 2 pounds of gold, 3 ticks of feather beds with the bolster therefor...

1707 - John Jones of Virginia leaves his daughter ... a feather bed one iron pott one Cow and calfe...

1765 - Sarah Gassaway of Maryland leaves her granddaughter her best feather bed and furniture and a piece of silk tissue and silk lining

History of Featherbeds & Duvets

Feather ticks, beds & mattresses

Featherbeds were only for the rich in the 14th century,

but by the 19th century they were a comfort that ordinary people could aspire to

- especially if they kept a few geese. The beds, also called feather ticks or feather

mattresses, were valuable possessions. People made wills promising them to the next

generation, and emigrants travelling to the New World from Europe packed up bulky

featherbeds and took them on the voyage. If you didn't inherit one, you needed to

buy up to 50 pounds of feathers, or save feathers from years of plucking until there

were enough for a new bed.

Featherbeds were only for the rich in the 14th century,

but by the 19th century they were a comfort that ordinary people could aspire to

- especially if they kept a few geese. The beds, also called feather ticks or feather

mattresses, were valuable possessions. People made wills promising them to the next

generation, and emigrants travelling to the New World from Europe packed up bulky

featherbeds and took them on the voyage. If you didn't inherit one, you needed to

buy up to 50 pounds of feathers, or save feathers from years of plucking until there

were enough for a new bed.

1847 prices for a pound of feathers at the London furniture store of Heal & Son

The feathers could be saved from geese or ducks being prepared for cooking. In England servant-girls were often allowed to keep feathers from poultry they'd plucked, and could save them to make a featherbed or pillows for their future married life. Live birds might have their soft downy breast feathers harvested three or four times a year, as described in an account from 20th century Missouri. Some poultry feathers were undesirable for mattress-making, especially chicken feathers. The best featherbeds were filled with a high proportion of down; larger feathers needed to have their quills clipped.

Lengthy preparation and good aftercare were essential. Before use, all feathers and down had to be aired outdoors in sun and breeze, or stoved indoors in a warm dry space; this would reduce smell and eliminate damp. Even so, there could be what Harriet Beecher Stowe called "the strong odor of a new feather-bed and pillows". The big London furniture store whose feather prices are listed above left, offered to clean and "purify" old beds with new steam machinery. They said this would remove the "offensive properties of the Quill" and also the "unpleasant smell of the stove" which affected all feathers prepared the usual way. They claimed the process would expand and bulk up feathers to make the bed much softer.

Feather beds should be opened every third year, the ticking well dusted, soaped, and waxed, the feathers dressed and returned.

R.K.Philp, Enquire Within Upon Everything (1869)

Why call them feather ticks? A tick is simply a linen or cotton bag filled with feathers - or straw or wool or cotton - and sewn shut. The fabric, called ticking, needed to be closely-woven to avoid feathers leaking out. Often the ticking was waxed, or rubbed with soap, to help keep it impenetrable.

Feather ticks

were not often used alone, but were laid over a firmer, non-feather mattress, as

in the picture to the left, where a white feather mattress is spread on top of the

striped under-mattress. Because the mattresses were just bags with no inner structure,

they needed shaking and re-shaping every morning. Learning to plump and smooth the

bed well was one of the arts of housekeeping.

Feather ticks

were not often used alone, but were laid over a firmer, non-feather mattress, as

in the picture to the left, where a white feather mattress is spread on top of the

striped under-mattress. Because the mattresses were just bags with no inner structure,

they needed shaking and re-shaping every morning. Learning to plump and smooth the

bed well was one of the arts of housekeeping.

Featherbeds were criticised by a few 19th century writers who felt they were unhealthy: too warm, too soft, too self-indulgent. Florence Nightingale said simply, "Never use a feather bed, either for sick or well". Some people chose to put their feather tick under a straw, horsehair or flock mattress in order to have a firmer or cooler bed.

Duvets, eiderdowns

With a feather-bed beneath and a bed of feathers on top, it must be admitted that the beds are warm enough—especially in summer.

J. Ross Browne, An American Family in Germany (1866)

Having a feather tick on top of you, as well as under you, was the perfect way of keeping warm at night during a northern European winter. For some reason the British only adopted the feathers-on-top custom very recently, and the writings of English-speaking travellers in Germany often comment on the "foreign" featherbeds used instead of blankets. Sometimes American pioneers describe sleeping between two feather ticks as a way of coping with extreme cold, and some immigrants must have been used to this custom in their home country. Yet it was only in the late 20th century that the English-speaking world started to adopt the duvet, sometimes called the continental quilt in England, associating it firmly with other parts of the European continent.

Duvets, known as federbetten or featherbeds in German, are loosely quilted. Broad channels stop the feathers ending up in one corner of the tick, while allowing them to expand and hold warm air. One eminent English traveller, Paul Rycaut, who tried and failed to introduce the duvet to his compatriots around 1700, sent his friends six-pound bags of down, explaining that "the coverlet must be quilted high and in large panes, or otherwise it will not be warme". Sixty years later Samuel Johnson described an unusual advertisement for: "some Duvets for bed-coverings, of down ... warmer than four or five blankets, and lighter than one." Still, they didn't catch on on his side of the English Channel, but 100 years later the "eider down quilt" was starting to become better-known.

Eiderdowns, or eider down quilts, were introduced to Victorian Britain as a marvellously light and warm substitute for heavy woollen blankets - but they didn't do away with all blankets. British beds were still made up with a top sheet, a couple of blankets and then an eiderdown: always an ornamental item, even when covered by a bedspread. The typical eiderdown was covered in satin or floral chintz, and tightly quilted. Despite its name it might well be filled with goose feathers, not real eider down from the eider duck.

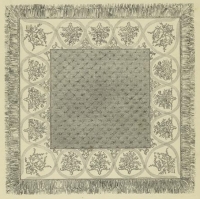

Crimson satin eider down quilt, with white satin borders

Shown at the 1851 Great Exhibition in London by Messrs. Heal & Son

The eider down quilt pictured is an elaborate quilt-bedspread combination created for the 1851 Great Exhibition. It is in a tradition stretching back to the Middle Ages of showy counterpanes/coverlets for rich people, and is not very like the warm feather duvets used in other parts of Northern Europe.

True duvets have a washable cover made of sheeting and are used with nothing but a bottom sheet and pillows. In the US the cover is sometimes called the duvet, and the inside a down comforter. A comforter, once also known as a comfortable, can also be a decorative and warm bed-cover like the eiderdown, used on top of a blanket. In the 1970s the great conversion to duvets started in the UK, and many businesses offered to convert your old eiderdown to a duvet. The US heard about duvets somewhat later - perhaps they were of less interest to a country with warm bedrooms and its own vigorous quilt traditions?

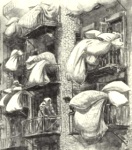

In

many countries, airing the duvet involves hanging it out of the window. This still

happens, as this recent photograph from Switzerland (left) shows. A drawing of the

same practice in an immigrant quarter of late 19th century New York (right) suggests

it seemed surprising, perhaps even comic, to some people.

In

many countries, airing the duvet involves hanging it out of the window. This still

happens, as this recent photograph from Switzerland (left) shows. A drawing of the

same practice in an immigrant quarter of late 19th century New York (right) suggests

it seemed surprising, perhaps even comic, to some people.

Airing featherbeds of the "mattress" kind was important to preserve them and keep them fresh. Stripping the bed, and shaking and turning them every morning helped a lot. 19th century housekeeping books in English sometimes also recommend complicated ways of propping them up for an hour or so to let them air - but not in the window, German style.

2006

2006

You may like our new sister site Home Things Past where you'll find articles about antiques, vintage kitchen stuff, crafts, and other things to do with home life in the past. There's space for comments and discussion too. Please do take a look and add your thoughts. (Comments don't appear instantly.)

For sources please refer to the books page, and/or the excerpts quoted on the pages of this website, and note that many links lead to museum sites. Feel free to ask if you're looking for a specific reference - feedback is always welcome anyway. Unfortunately, it's not possible to help you with queries about prices or valuation.