-

History of:

- Resources about:

- More:

- Baby walkers

- Bakehouses

- Bed warmers

- Beer, ale mullers

- Besoms, broom-making

- Box, cabinet, and press beds

- Butter crocks, coolers

- Candle snuffers, tallow

- Clothes horses, airers

- Cooking on a peat fire

- Drying grounds

- Enamel cookware

- Fireplaces

- Irons for frills & ruffles

- Knitting sheaths, belts

- Laundry starch

- Log cabin beds

- Lye and chamber-lye

- Mangles

- Marseilles quilts

- Medieval beds

- Rag rugs

- Rushlights, dips & nips

- Straw mattresses

- Sugar cutters - nips & tongs

- Tablecloths

- Tinderboxes

- Washing bats and beetles

- Washing dollies

- List of all articles

Subscribe to RSS feed or get email updates.

You should always boil your starch in a copper vessel, because as it requires a great deal of boiling, tin is very apt to make it burn to.

c1770, The complete servant maid: or young woman's best companion, Anne Barker

Renaissance Clothing and the Materials of Memory, by Ann Jones and Peter Stallybrass - with a chapter on yellow starch

from Amazon.comor Amazon UK

Best Poland starch 15 pence a pound

Grocer's price list, London 1800

COLD STARCH FOR LINEN - Take a quarter of a pint, or as much of the best raw starch as will half fill a common-sized tumbler. Fill it nearly up with very clear cold water. Mix it well with a spoon, pressing out all the lumps, till you get it thoroughly dissolved, and very smooth. Next add a tea-spoonful of salt to prevent its sticking. Then pour it into a broad earthen pan; add, gradually, a pint of clear cold water; and stir and mix it well. Do not boil it. The shirts having been washed and dried, dip the collars and wristbands into this starch, and then squeeze them out. Between each dipping, stir it up from the bottom with a spoon. Then sprinkle the shirts, and fold or roll them up, with the collars and wristbands folded evenly inside. They will be ready to iron in an hour. This quantity of cold starch is amply sufficient for the collars and wristbands of half a dozen shirts. Any article of cambric muslin may be done up with cold starch made as above. Poland starch is better than any other. It is to be had at most grocery stores. Cold starch will not do for thin muslin, or for any thing that is to be clapped and cleared. It is very convenient for linen etc., in summer, as it requires no boiling over the fire. Also, it goes farther than boiled starch.

Lady's Recipt Book, Eliza Leslie, 1850

1930s, San Diego, California:

The starch came in chunks up to the size of golf balls, which was put into a bowl with boiling water to dissolve, or cooked on the stove and made into a thick slimy solution. Items were then swirled in the milky looking starch, wrung out and hung on the line. Jacquelyn M. Shepard, The Seasons of My Life: A Family History, 2003

History of starching fabric

Laundry starch: from medieval luxury to Victorian mass market

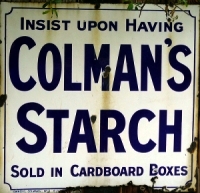

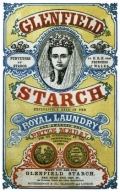

Starch has come a long way: from

a sour mix boiled and brewed to a press-button spray. Manufactured starch that could

be conveniently mixed at home as "cold starch" without boiling was available by

the 19th century, suitable for clothes that didn't need a perfectly clear starch

mixture. Victorian science and new styles of commerce made starch into a branded

product. Buying it neatly packaged instead of in lumps was not just convenient;

it suggested a "modern", well-prepared formula. No wonder one company made its selling

point, from about 1881, the cardboard box its starch was sold in. (See advertising

photo right)

Starch has come a long way: from

a sour mix boiled and brewed to a press-button spray. Manufactured starch that could

be conveniently mixed at home as "cold starch" without boiling was available by

the 19th century, suitable for clothes that didn't need a perfectly clear starch

mixture. Victorian science and new styles of commerce made starch into a branded

product. Buying it neatly packaged instead of in lumps was not just convenient;

it suggested a "modern", well-prepared formula. No wonder one company made its selling

point, from about 1881, the cardboard box its starch was sold in. (See advertising

photo right)

It's often said that starching was "introduced" in the 16th century when it was essential for fine ruffs and fluted collars, but that's not accurate. Starch was already in use for fine linens and laces, but in the 1500s starchmaking became more organised and commercial in Northern Europe. Flanders, home of the famous Flemish lace, was one of the earliest centres of starch manufacturing and skilful use. A Dutchwoman brought some of that knowledge to Elizabethan London, and set herself up as an expert at a time when there was high demand for well laundered and elaborate collars and cuffs. And that's why some websites tell us that starch "arrived" in 1564.

Early use of starch

Laundry was not a hot topic for medieval writers and there's not a lot known about

it before the age of ruffs. The first clues in English are from the 14th century.*

Then 'starch for kerchiefs' appeared in a 1440 dictionary.* Also around 1440, we

know the nuns of Syon Abbey were starching altar cloths and other church linens.

Only starch "made of herbes" could be used for communion linen.* This was probably

prepared from the roots of the cuckoo-pint flower (arum maculatum or starchwort):

Laundry was not a hot topic for medieval writers and there's not a lot known about

it before the age of ruffs. The first clues in English are from the 14th century.*

Then 'starch for kerchiefs' appeared in a 1440 dictionary.* Also around 1440, we

know the nuns of Syon Abbey were starching altar cloths and other church linens.

Only starch "made of herbes" could be used for communion linen.* This was probably

prepared from the roots of the cuckoo-pint flower (arum maculatum or starchwort):

The most pure and white starch is made of the rootes of the Cuckoo-pint, but most hurtful for the hands of the laundresse that have the handling of it, for it chappeth, blistereth, and maketh the hands rough and rugged and withall smarting.

Gerard's Herbal, 1633

Ordinary starch was made by boiling bran in water, then letting it stand for three days, according to a 15th century recipe.* Once the bran had been strained out, cloth was dipped in the sour, starchy water, dried, then smoothed and polished with a slickstone. For obvious reasons starch was a bit of a luxury. Who had time for all that? Although professional 'starchers' existed before elaborate ruffs came into fashion*, from that time on there were more starchmakers, and more laundresses who could handle fine lawn and cambric trimmings.

Coloured starch

The 17th century saw a controversial fashion for ruffs laundered with "yellow starch",

and then red or green starch. In London this provoked disapproval, mockery, and

was linked with scandal. (See

Renaissance Clothing

The 17th century saw a controversial fashion for ruffs laundered with "yellow starch",

and then red or green starch. In London this provoked disapproval, mockery, and

was linked with scandal. (See

Renaissance Clothing.)

The best-known colour was also the earliest: blue starch.

Used in moderation, this made whites seem whiter, and not blue at all.

Tinted starch came back in Victorian times. Packeted écru and buff sold well for use on blonde lace and beige/cream colours, while blue starch continued popular for brightening whites. More unusual colours were marketed but didn't sell as well.

JUST LANDED: Reckitt's COLOURED STARCH, Pink, Ecru, Heliotrope, in boxes 6d. each, far superior to any other brands.

The Mercury, Hobart, Tasmania, 1896

Gloss, glaze, and gleam

Recipes and household tips from the past remind us that most fabrics looked limp

and crumpled after laundering. There were special instructions for starching delicate,

droopy muslins. Starch helped make clothes and table linen firmer and glossier,

and you could add extra ingredients for an even better finish. A little candle grease

or cooking fat went into starch mixtures for more gloss. Salt was the most common

ingredient recommended for helping the ironing to go smoothly.

Recipes and household tips from the past remind us that most fabrics looked limp

and crumpled after laundering. There were special instructions for starching delicate,

droopy muslins. Starch helped make clothes and table linen firmer and glossier,

and you could add extra ingredients for an even better finish. A little candle grease

or cooking fat went into starch mixtures for more gloss. Salt was the most common

ingredient recommended for helping the ironing to go smoothly.

There are various things which diferent people mix with their starch, such as alum, gum arabic, and tallow, but if you do put anything in, let it be a little isinglass, for that is by far the best. About an ounce to a quarter of a pound of starch will be sufficient.

The complete servant maid: or young woman's best companion. Containing full, plain, and easy directions..., Anne Barker, c1770

All the well-known recipes were imitated

by 19th and 20th century manufacturers who emphasised gloss in their advertising

and chose brand names like Fairy Glaze. Borax was often added to increase gloss.

Not sticking to the iron and ease of mixing were other key qualities. Added bluing

was a desirable extra for use on white laundry. However much soaking, boiling, scrubbing

and bleaching you did, blue would make whites gleam more brightly.

All the well-known recipes were imitated

by 19th and 20th century manufacturers who emphasised gloss in their advertising

and chose brand names like Fairy Glaze. Borax was often added to increase gloss.

Not sticking to the iron and ease of mixing were other key qualities. Added bluing

was a desirable extra for use on white laundry. However much soaking, boiling, scrubbing

and bleaching you did, blue would make whites gleam more brightly.

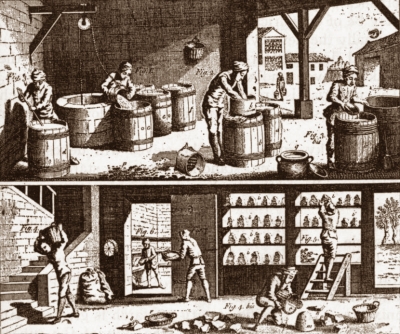

Starchmaking could take up to a month, with long boiling, soaking, draining, rinsing,

drying and so on. In the 17th century the use of wheat was criticised as wasting

food on fashion. The 18th century saw experimentation with different sources of

starch, including horse chestnuts and potatoes. In the 19th century new ingredients

and manufacturing methods were developed in the quest for pure white, refined starch.

Rice starch was considered to give a good glazed finish. Corn starch made a more

opaque mixture but could be made at home. There were recipes for this and other

starches in US domestic advice manuals. It was also used in North American branded

laundry starch products: often called "gloss starch" to distinguish it from cooking

starch.

Starchmaking could take up to a month, with long boiling, soaking, draining, rinsing,

drying and so on. In the 17th century the use of wheat was criticised as wasting

food on fashion. The 18th century saw experimentation with different sources of

starch, including horse chestnuts and potatoes. In the 19th century new ingredients

and manufacturing methods were developed in the quest for pure white, refined starch.

Rice starch was considered to give a good glazed finish. Corn starch made a more

opaque mixture but could be made at home. There were recipes for this and other

starches in US domestic advice manuals. It was also used in North American branded

laundry starch products: often called "gloss starch" to distinguish it from cooking

starch.

Even when some starch could be used "cold", home boiling with water and other additives continued. It depended not only on the type of starch but on the kind of fabric, the judgment of the launderer etc. etc. Some starch mixes were milky and more suitable for thicker fabrics. Good laundresses were expected to "clear-starch": preparing transparent starch mixtures and knowing how to use them. Clear-starching meant keeping delicate muslin and similar fabrics from being clogged with starch granules in the loose weave, and avoiding thickening caused by visible traces of starch clinging to the threads.

Historical references:

Historical references:

* Earliest in English c1390, church records from Norwich list eightpence

for "vestiarium: pro coole, pro starchyng"

* Starch for kerchiefs "starche, for kyrcheys" in Promptorium parvulorum

sive clericorum: dictionarius anglo-latinus princeps, by Galfridus Anglicus (dominican

friar), c1440 - also

* Instructions for nuns laundering from c1440 in George Aungier's The History

and Antiquities of Syon Monastery, 1840

* Recipe is in Sloane MS 3548

* Professional starchers: "Butlers, sterchers, and musterde makers;

Harde ware men, mole sekers, and ratte takers;"

from Cock Lorelle's Bote - ballad c1515

Harold Auden, Starch and Starch Products, London, 1922

Traditional laundry starch powders available in the US and the UK

Argo Gloss Laundry Starch from Amazon.com

Kershaw's Traditional Laundry Starch from Amazon UK

See also:

See also:

History of Laundry: washing and drying

How muslin clothes were starched

History of Ironing

Site map with full list of laundry articles

21 July 2010

21 July 2010

You may like our new sister site Home Things Past where you'll find articles about antiques, vintage kitchen stuff, crafts, and other things to do with home life in the past. There's space for comments and discussion too. Please do take a look and add your thoughts. (Comments don't appear instantly.)

For sources please refer to the books page, and/or the excerpts quoted on the pages of this website, and note that many links lead to museum sites. Feel free to ask if you're looking for a specific reference - feedback is always welcome anyway. Unfortunately, it's not possible to help you with queries about prices or valuation.