-

History of:

- Resources about:

- More:

- Baby walkers

- Bakehouses

- Bed warmers

- Beer, ale mullers

- Besoms, broom-making

- Box, cabinet, and press beds

- Butter crocks, coolers

- Candle snuffers, tallow

- Clothes horses, airers

- Cooking on a peat fire

- Drying grounds

- Enamel cookware

- Fireplaces

- Irons for frills & ruffles

- Knitting sheaths, belts

- Laundry starch

- Log cabin beds

- Lye and chamber-lye

- Mangles

- Marseilles quilts

- Medieval beds

- Rag rugs

- Rushlights, dips & nips

- Straw mattresses

- Sugar cutters - nips & tongs

- Tablecloths

- Tinderboxes

- Washing bats and beetles

- Washing dollies

- List of all articles

Subscribe to RSS feed or get email updates.

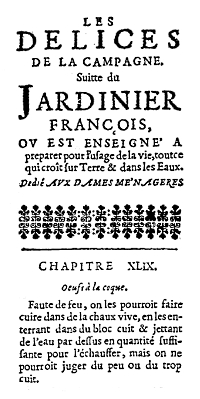

The Pleasures of the Countryside, sequel to the French Gardener, with instructions for everyday preparation of all that grows on earth or in water.

Dedicated to housewives ...

Oeufs à la coque

Soft-boiled eggs (or literally, eggs in the shell.)

In the absence of fire, you could cook them in quicklime, burying them in it, and throwing water over in sufficient quantity to heat it up, but you will not be able to judge whether they are cooked too little or too much.

Nicolas de Bonnefons, Les Délices de la Campagne, c1651 (see illustration)

Pleyn Delit: Medieval Cookery for Modern Cooks by Hieatt, Hosington, and Butler, from Amazon.comor Amazon UK

She seasons the young lambs and puts them in three lidded cooking-pots, well-sealed, in the middle of a basin in which she puts quicklime. She pours water on the quicklime which starts to boil up. The tender lamb meat begins cooking in the pots.

Traditional Tunisian tale, from Contes de Ghzalaby Myriam Houri-Pasotti

Lime power for cooking - medieval pots to 21st century cans

Quicklime fireless cooking, slaking lime with water for heat without fire

I was intrigued to discover a medieval

version of today's self-heating cans of soup, beans, and coffee. In a Welsh museum

is an Anglo-Norman double

pot, a smaller cooking

pot inside a bigger one, designed for cooking without any need for lighting

a fire.

In the space between the two pots you could set off a chemical reaction by mixing

chunks of quicklime (photo right) with water. It created heat to cook the food inside

the sealed inner pot.

I was intrigued to discover a medieval

version of today's self-heating cans of soup, beans, and coffee. In a Welsh museum

is an Anglo-Norman double

pot, a smaller cooking

pot inside a bigger one, designed for cooking without any need for lighting

a fire.

In the space between the two pots you could set off a chemical reaction by mixing

chunks of quicklime (photo right) with water. It created heat to cook the food inside

the sealed inner pot.

Quicklime, also called lime

or unslaked lime, is what's inside many of today's self-heating cans too. (More

explanation at bottom of page.)

Quicklime, also called lime

or unslaked lime, is what's inside many of today's self-heating cans too. (More

explanation at bottom of page.)

A recipe from 13th century England explains how to cook with a pair of pots and no fire. It really was cooking, not just heating up pre-cooked food and drink:

To cook meat without fire....

Take a small earthenware pot with earthenware lid of the right size. Then take another pot, also earthenware, also with a suitable lid that fits well. This should be five fingers deeper than the first, and three fingers bigger round. Then take pork and chicken, cut them into nice pieces, get good spices and put them in, and some salt. Take the little pot with the meat in and put it inside the big pot. Set it upright, cover it with the lid and seal with damp, sticky soil, so nothing can come out. Then take lime that has not been slaked [quicklime], put it in the big pot full of water, but take care that no water gets into the small pot. Leave it alone for as long as it takes to go five to seven leagues. Then open your pots, and you will find your meat well and truly cooked.

The original late 13th century recipe in French (A quire char saunz fu/A cuire chair sans feu) is in Hieatt and Jones' Two Anglo-Norman Culinary Collections

So who cooked this way? Was lime cooking for medieval outdoorsmen like the modern

explorers, soldiers, and campers who carry survival rations in self-heating food

packs? Is the "five to seven leagues" a clue that the recipe was for people

who would walk fifteen to twenty miles while their dinner was cooking and had no

time to sit tending a fire? How did the meat go on cooking once the lime and water

reaction died down? Was the pot insulated with grass or earth?

So who cooked this way? Was lime cooking for medieval outdoorsmen like the modern

explorers, soldiers, and campers who carry survival rations in self-heating food

packs? Is the "five to seven leagues" a clue that the recipe was for people

who would walk fifteen to twenty miles while their dinner was cooking and had no

time to sit tending a fire? How did the meat go on cooking once the lime and water

reaction died down? Was the pot insulated with grass or earth?

Cooking an egg in lime and water doesn't need a fancy double pot, since the shell keeps the food and chemicals separate. One method is described in a popular French cookery book from the 1650s (see left-hand column), but the idea is much older. An early description of an egg cooked in a potful of water and lime seems to have come from the 10th century Persian scholar al-Razi, once known in Europe as Rasis. He treated it more like a magic trick than kitchen cookery.

Quicklime cooking took on a scientific tone in an early Victorian demo at the London

Gallery of Practical Science. Here the "chemical

lecturer" had apparatus for cooking a steak. The meat, which was cut up for the

audience to taste, looked like boiled beef but had the "richness of a broiled rump

steak" according to the Oxford Herald in 1836.

Quicklime cooking took on a scientific tone in an early Victorian demo at the London

Gallery of Practical Science. Here the "chemical

lecturer" had apparatus for cooking a steak. The meat, which was cut up for the

audience to taste, looked like boiled beef but had the "richness of a broiled rump

steak" according to the Oxford Herald in 1836.

The most novel matter was a lecture by Mr. [William] Maugham, on an apparatus for cooking without fire. The experiment was shewn with a tin box, in the centre of which was a drawer, where beefsteaks and eggs were deposited. In the compartments, above and below, lime was placed, and slaked with water. The usual process took place, heat was disengaged, and the victuals were perfectly dressed, without receiving any peculiar flavour or taste from the means employed. ... The operation took about half an hour.

Literary Gazette, January 1835

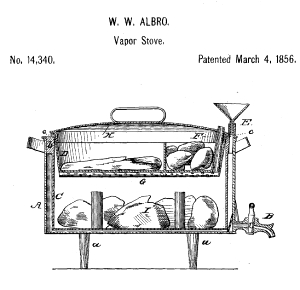

Twenty years later in the USA, a "vapor stove" for cooking a full meal plus coffee

(see the handy faucet!) with lime heat only was patented by W.W. Albro of Binghamton,

Broome County, NY.

Twenty years later in the USA, a "vapor stove" for cooking a full meal plus coffee

(see the handy faucet!) with lime heat only was patented by W.W. Albro of Binghamton,

Broome County, NY.

Coffee or tea is made in the space between the two vessels A C. Meat and vegetables are placed within the dish or vessel D, which may be provided with partitions to separate the different articles. A requisite quantity of quicklime is placed within the vessel C and the cover H is placed over the dish or vessel D. A requisite quantity of water is then poured [in and] falls through the perforated tube G in a shower upon the quicklime....

From then on there

were plenty more attempts to harness the power of slaking lime with water to cook

food away from home and hearth. This generally seems to have been an experiment,

not part of ordinary life, despite optimistic remarks in patents about the convenience

of being able to cook away from a kitchen or campfire.

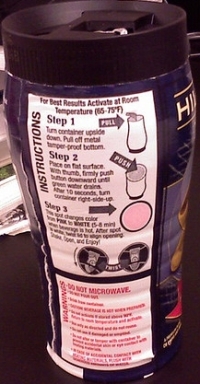

Self-heating cans for ready-made soup etc., which came on the scene around

1900, were useful for special situations like war and travel by air balloon. The

most recent cans

have a simple push-button to trigger the heat-creating reaction. Other chemicals

as well as lime have been tried for self-heating food and drink.

From then on there

were plenty more attempts to harness the power of slaking lime with water to cook

food away from home and hearth. This generally seems to have been an experiment,

not part of ordinary life, despite optimistic remarks in patents about the convenience

of being able to cook away from a kitchen or campfire.

Self-heating cans for ready-made soup etc., which came on the scene around

1900, were useful for special situations like war and travel by air balloon. The

most recent cans

have a simple push-button to trigger the heat-creating reaction. Other chemicals

as well as lime have been tried for self-heating food and drink.

With all the disposable packaging as well as the energy used to make quicklime, the cans are nothing like a green new way of cooking, even though they use no firewood and no electricity. But if you could make a safe low-tech lime stove, and use solar energy to "recharge" the slaked lime, turning it back into quicklime.... Yes, some people are working on a "rechargeable solar stove". A long way from a medieval earthenware double-wall cooking pot found on the English-Welsh border?

Quicklime

has been known for thousands of years. It is made by heating limestone to high temperatures

in a lime kiln. Slaking it, or mixing it with water, produces heat. The

slaked lime is a traditional ingredient in mortar, plaster, and whitewash,

and has many other uses.

Quicklime

has been known for thousands of years. It is made by heating limestone to high temperatures

in a lime kiln. Slaking it, or mixing it with water, produces heat. The

slaked lime is a traditional ingredient in mortar, plaster, and whitewash,

and has many other uses.

Don't try heating food with lime if you're not sure how to do it safely. Handling lime is dangerous unless you are experienced with such chemicals. Skin contact or inhalation can cause severe reactions.

- Some other pages about cooking and food:

- Baking over an open fire: bannocks and flat breads

- Baking peels and paddles

- Hasteners and meat screens

- Pressure cookers

- Sugar nips or nippers

10 Aug 2010

10 Aug 2010

You may like our new sister site Home Things Past where you'll find articles about antiques, vintage kitchen stuff, crafts, and other things to do with home life in the past. There's space for comments and discussion too. Please do take a look and add your thoughts. (Comments don't appear instantly.)

For sources please refer to the books page, and/or the excerpts quoted on the pages of this website, and note that many links lead to museum sites. Feel free to ask if you're looking for a specific reference - feedback is always welcome anyway. Unfortunately, it's not possible to help you with queries about prices or valuation.