-

History of:

- Resources about:

- More:

- Baby walkers

- Bakehouses

- Bed warmers

- Beer, ale mullers

- Besoms, broom-making

- Box, cabinet, and press beds

- Butter crocks, coolers

- Candle snuffers, tallow

- Clothes horses, airers

- Cooking on a peat fire

- Drying grounds

- Enamel cookware

- Fireplaces

- Irons for frills & ruffles

- Knitting sheaths, belts

- Laundry starch

- Log cabin beds

- Lye and chamber-lye

- Mangles

- Marseilles quilts

- Medieval beds

- Rag rugs

- Rushlights, dips & nips

- Straw mattresses

- Sugar cutters - nips & tongs

- Tablecloths

- Tinderboxes

- Washing bats and beetles

- Washing dollies

- List of all articles

Subscribe to RSS feed or get email updates.

Magic of Fire: Hearth Cooking: One Hundred Recipes for the Fireplace or Campfire, by William Rubel, from Amazon.com

The sort of roasting machine, called the Poor Man's Spit, is something [like a bottle jack], but still more simple. The meat is suspended by a skein of worsted, a twirling motion being given to the meat, the thread is twisted, and when the force is spent, the string untwists itself two or three times alternately, till the action being discontinued, the meat must again get a twirl round. When the meat is half done, the lower extremity of the joint is turned uppermost, and affixed to the string, so that the gravy flows over the joint the reverse way it did before.

The American Farmer: Ladies' Department, November 1825

Cooking in Europe, 1250-1650, by Ken Albala from Amazon.comor Amazon UK

Patrick Dunne, The Epicurean Collector: Exploring the World of Culinary Antiques, from Amazon.comor Amazon UK

Walter Dunn, People of the American Frontier: The Coming of the American Revolution, from Amazon.comor Amazon UK

Roasting meat hanging in front of a fire

Roasting jacks - from string to clockwork

The Victorians used splendid brass

clockwork jacks for spinning roasting joints of meat slowly round in front of a

fire. These bottle jacks (named for their shape), or clock jacks, make fine antiques

and are interesting to food historians, but we should not end up with the impression

that this was the "normal" way of roasting meat in the 19th century, let alone before.

It's true that clockwork bottle jacks gradually became more and more common for meat hung

up to roast during the 18th and 19th centuries. By the later 19th century you could

buy an iron bottle-jack for six shillings in England, the country where these were

especially popular. This meant professional homes could afford one, but plenty of

middle-class people managed with simpler methods of roasting, while clockwork jacks

remained unaffordable for the working classes.

The Victorians used splendid brass

clockwork jacks for spinning roasting joints of meat slowly round in front of a

fire. These bottle jacks (named for their shape), or clock jacks, make fine antiques

and are interesting to food historians, but we should not end up with the impression

that this was the "normal" way of roasting meat in the 19th century, let alone before.

It's true that clockwork bottle jacks gradually became more and more common for meat hung

up to roast during the 18th and 19th centuries. By the later 19th century you could

buy an iron bottle-jack for six shillings in England, the country where these were

especially popular. This meant professional homes could afford one, but plenty of

middle-class people managed with simpler methods of roasting, while clockwork jacks

remained unaffordable for the working classes.

The poorest people could either take

meat to be roasted (or, strictly speaking, baked) at

the local bakehouse, or fix it on a wound-up string before the fire, and

re-wind it every few minutes. The most suitable thread was "worsted", made of strands

twisted closely together. String roasting works particularly well with poultry and

game birds, as shown in this video.

The poorest people could either take

meat to be roasted (or, strictly speaking, baked) at

the local bakehouse, or fix it on a wound-up string before the fire, and

re-wind it every few minutes. The most suitable thread was "worsted", made of strands

twisted closely together. String roasting works particularly well with poultry and

game birds, as shown in this video.

Of course there were ways of roasting by a fire that were more sophisticated than string hung over a nail, yet cheaper and simpler than the clockwork contraptions. (And also much simpler than the smoke-jacks available for bigger chimneys, or clockwork-driven horizontal spits.) From the 17th century at least you could buy ironmongery for "hang roasting" small birds and joints. Similar things are on sale today in countries like France and Italy where game bird hunting is popular.

Although there are a variety of contrivances for roasting, very many families are unprovided with any kind of apparatus for conducting the business. A very cheap and simple arrangement, and which will answer the purpose as well as more costly and complicated machinery, is to roast by the string. Mrs. Hill's Southern Practical Cookery and Recipe Book, 1872

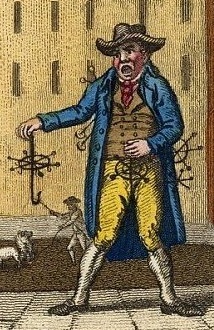

At one time simple iron roasting jacks were offered by street vendors in big cities, or available from a local blacksmith or ironmonger. Other names for simple hangers were dangle spits, dangle jacks, hanging jacks, poor man's jack, or poor man's spit. Dangle spits were also used for birds in large kitchens where there was a traditional spit too for big pieces of meat. Some were like the jacks in the picture below right. Others had a hook on the bottom of a metal strip with a cross-bar for two smaller hooks at each end. Annabella Hill, in her 1860s/70s cookbook from the American South, recommended a well-made hanger at the top but thought the rest of the arrangement could be very simple, as long as you had the "absolutely necessary" practice for good results:

Procure a piece of iron or steel eighteen inches long, with a hinge in the middle, to fold it out of the way when not in use. It should be strong enough to meet any demands made upon it ; at one end there should be a plate of iron three inches long and two wide, with screws inserted to fasten it to the mantel-piece. ... At the other end a twirling hook, or common ring and hook; take a twine or twisted woollen string long enough to bring the articles to be cooked before the full influence of the fire. A hook should be securely fastened to each end of this string; catch one hook to the twirling hook, the other insert in the meat.

A domestic advice compendium

published in both the US and UK in the 1850s said that a weight

should be used when string roasting. (Picture below left) You could fill a metal container with sand or

tie a stone on the string.

A domestic advice compendium

published in both the US and UK in the 1850s said that a weight

should be used when string roasting. (Picture below left) You could fill a metal container with sand or

tie a stone on the string.

We should not omit the humble string and weight by means of which many a small joint or piece of meat is roasted by the simple twisting and untwisting of a worsted string: [the picture shows] a tin box filled with some heavy substance, and costs only sixpence. This will roast about six or eight pounds of meat, and two smaller hooks are added for less articles. The only objection is the attention necessary as the string requires a slight twist every five minutes.

Webster & Parkes, Encyclopaedia of Domestic Economy, 1852, London and Boston

Around the same time, the

famous chef Alexis Soyer

had positive things to say about low-tech ways of roasting. Like many other cooks

he made the point that clockwork jacks were not very reliable and often needed mending.

He also reminds us that vertical roasting was well-suited to narrow fireplaces.

Around the same time, the

famous chef Alexis Soyer

had positive things to say about low-tech ways of roasting. Like many other cooks

he made the point that clockwork jacks were not very reliable and often needed mending.

He also reminds us that vertical roasting was well-suited to narrow fireplaces.

...I used to roast very well with a bit of string. For the cottage kitchen, where there is no smoke-jack provided, you may roast very well with a piece of worsted or string, by hooking it to the meat, and then suspending it to a bracket fixed under the mantel-piece, which will enable you to remove it to any distance you think proper from the fire, making a tea-tray, at the distance of three feet from the fire, act as a screen; the bottle-jacks are not bad, but soon get out of repair.

Alexis Soyer, The Gastronomic Regenerator, 1849

This page is all about hanging

meat vertically for roasting, but the word jack also meant various wheel and chain

or rope set-ups that turned a horizontal spit on the hearth. As it says in the dictionary

(OED): "Applied to things which in some way take the place of a lad or man, or save

human labour [...] A machine for turning the spit in roasting meat". Traditional

spits, even those powered by advanced winding mechanisms, didn't suit "modernised"

19th century kitchens well, but of course they have never disappeared.

This page is all about hanging

meat vertically for roasting, but the word jack also meant various wheel and chain

or rope set-ups that turned a horizontal spit on the hearth. As it says in the dictionary

(OED): "Applied to things which in some way take the place of a lad or man, or save

human labour [...] A machine for turning the spit in roasting meat". Traditional

spits, even those powered by advanced winding mechanisms, didn't suit "modernised"

19th century kitchens well, but of course they have never disappeared.

We can get some idea of who used what from an 1874 advice manual aimed at different social layers of middle-class Britain. Its author recommended a household with an income that might belong to a successful lawyer to have a good brass bottle jack costing 25 shillings. They should team it with a tin-lined meat screen, complete with hot closet. The poorest household covered by his book, perhaps a low-ranking civil servant's family, were advised to buy a plain metal bottle-jack for 6 shillings and sixpence.

Despite this advice, which implied all his readers would want to roast meat hanging vertically, the writer thought a "horizontal spit, worked by the smoke-jack, [was] the most perfect". However, because it would be so noisy, he said you could not have one in a town house where the dining room was likely to be over the kitchen and too near the noise. It was also out of the question in smaller houses with narrow flues.

Roasting any kind of flesh or fowl was a primitive affair, but the settlers' simple method worked. ... Turning the roast could be accomplished using a peg, a string, and a stone. A peg was driven into the mantel...and one end of a stout worsted string was tied onto the peg. Meat...was trussed in the middle of the string. A stone was tied to the other end... ...The string was twisted taut, and the meat turned slowly as the string unwound and rewound....

Walter S. Dunn, People of the American Frontier: The Coming of the American Revolution, 2005

Other kitchen and food-related articles on this site include:

- Kitchen and culinary antiques - resources

- Baking over an open fire: bannocks and flat breads

- Baking peels and paddles

- Game pie dishes

- Hasteners and meat screens

- Pressure cookers

- Sugar nippers

- Tureens shaped like poultry

.....colonial America. In the May 2, 1737, issue of the Boston Gazette, John Jackson, jack-maker, offered made-to-order roasting implements at his shop at the town drawbridge. In addition to cookery supplies, he stocked ironing boxes and locks and keys and also cleaned and mended old jacks, which often bent from heavy loads or rusted from salty marinades. In 1784, clockmaker Simon Willard received his first patent from Massachusetts for making and selling his clock jack, a wind-up device that attached to a mantel and suspended haunches of meat or fowl from a hook to turn in a precise rhythm before the fire.

Mary Snodgrass, Encyclopedia of Kitchen History, 2004

11 May 2011

11 May 2011

You may like our new sister site Home Things Past where you'll find articles about antiques, vintage kitchen stuff, crafts, and other things to do with home life in the past. There's space for comments and discussion too. Please do take a look and add your thoughts. (Comments don't appear instantly.)

For sources please refer to the books page, and/or the excerpts quoted on the pages of this website, and note that many links lead to museum sites. Feel free to ask if you're looking for a specific reference - feedback is always welcome anyway. Unfortunately, it's not possible to help you with queries about prices or valuation.